The South Coast Style Endures: ‘bagan bariwariganyan: echoes of country’ at Bundanon

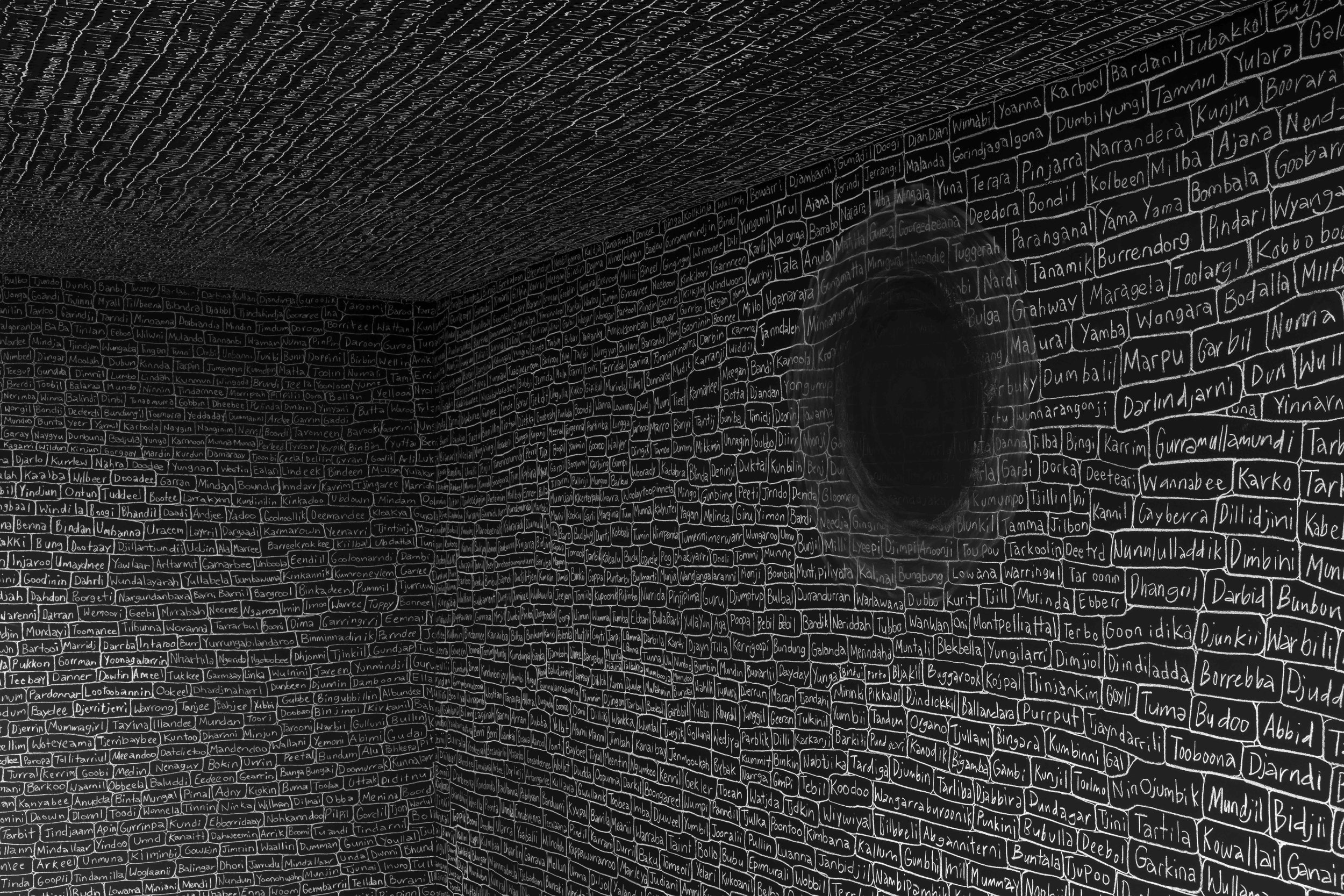

/Bundanon, nestled amid a dense forest of eucalypt, acacia and blackwood by the Shoalhaven River, is playing host to ‘bagan bariwariganyan: echoes of country’, an exhibition that brings together the works of four Indigenous artists: Walbunja and Ngarigo storyteller, singer and artist Aunty Cheryl Davison; Gweagal and Wandiwandian artist and knowledge-holder Aunty Julie Freeman; Mickey of Ulladulla; and Wiradjuri and Kamilaroi artist Jonathan Jones. The latter also features in the exhibition as a curator—he worked on the exhibition with Bundanon’s resident curator Boe-Lin Bastian. Together, these artists and curators have created a show that encapsulates the richness of South Coast Indigenous culture, effortlessly weaving together sculpture, soundscape, textiles, painting and mural work.

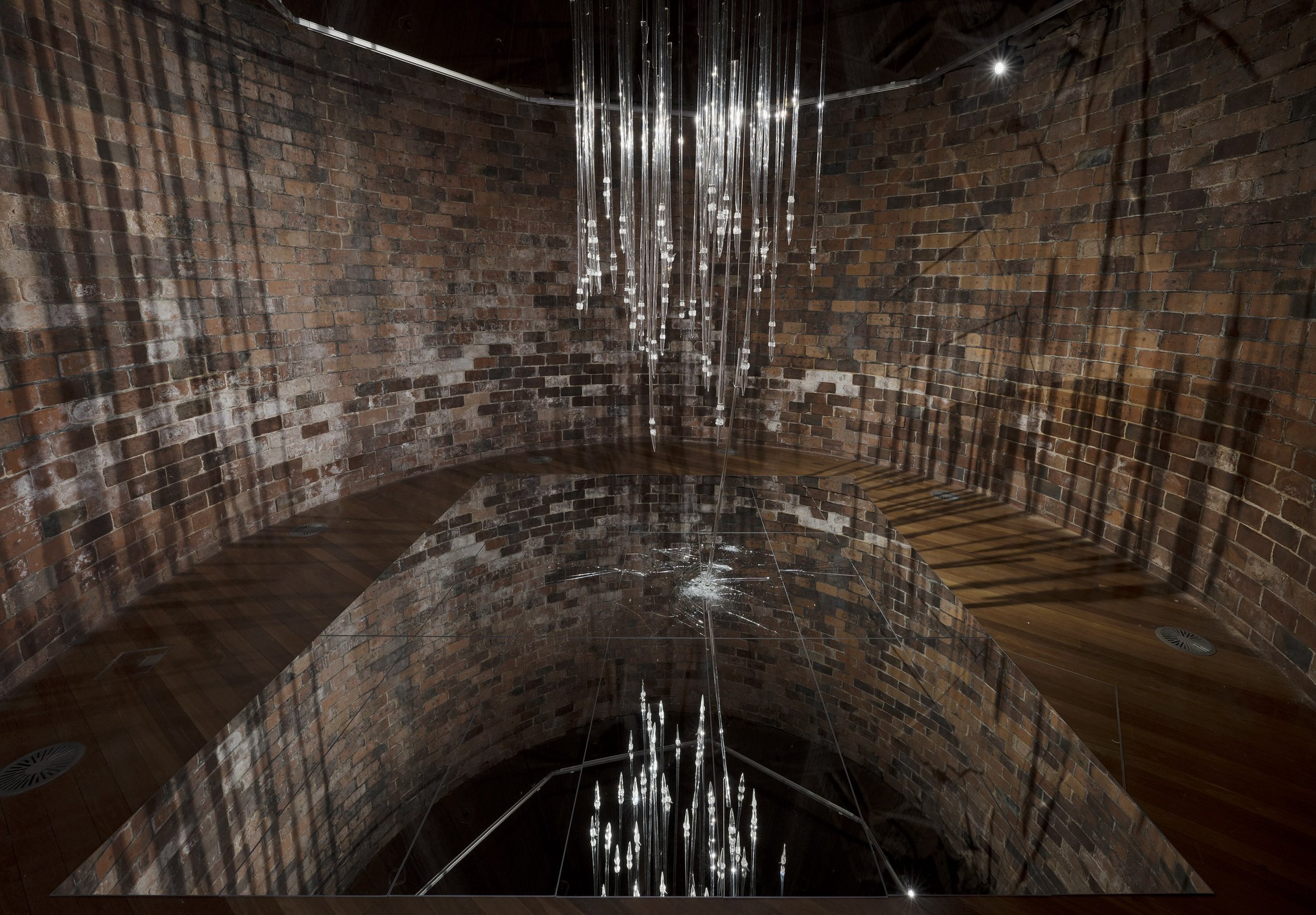

Jones talked in detail during the opening weekend about the cultural responsibility of being from neighbouring Wiradjuri Country and coming onto and working with Yuin Country and local story holders and artists. This care and consideration for cultural protocol is reflected in gunyah, a collaboration between Jones, Aunty Cheryl and Aunty Julie. Multiple turpentine trees (Syncarpia glomulifera) break up the space, representing an Indigenous way of understanding and constructing space. Standing tall, they uphold a sea of screen-printed works by Aunty Cheryl depicting the Glossy Black Cockatoo creation story. A rich soundscape of lightning, rumbling thunder and the swarming of glossies overhead plays on loop. Dispersed among a few elbow notches in turpentine trees hang Aunty Julie’s shell necklaces. Aunty Julie’s works speak to the enduring nature of traditional stories and cultural practices being passed down from her ancestors to her and subsequently to her daughter, Markeeta Freeman, who features as a collaborative artist on many of her mother’s works.

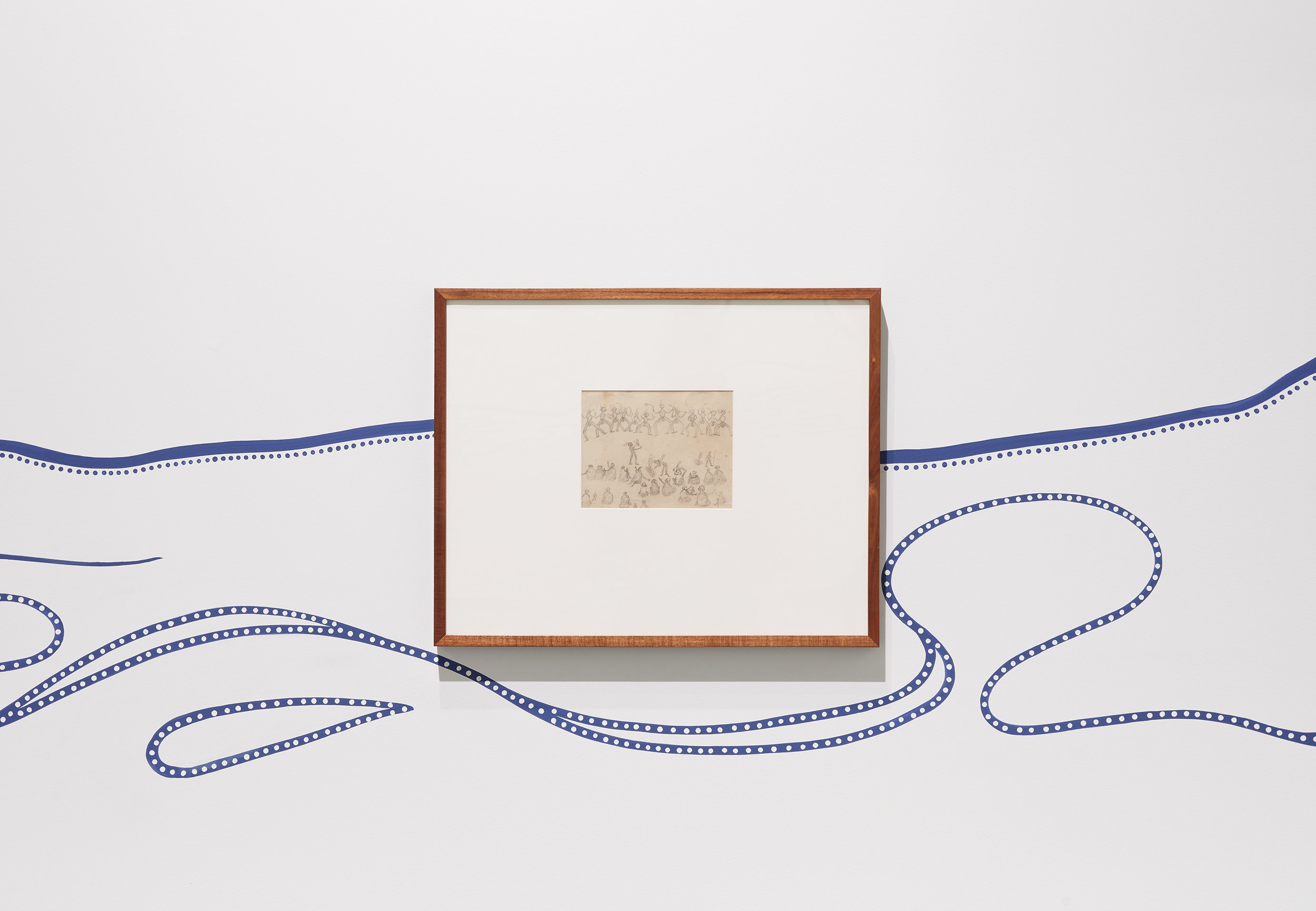

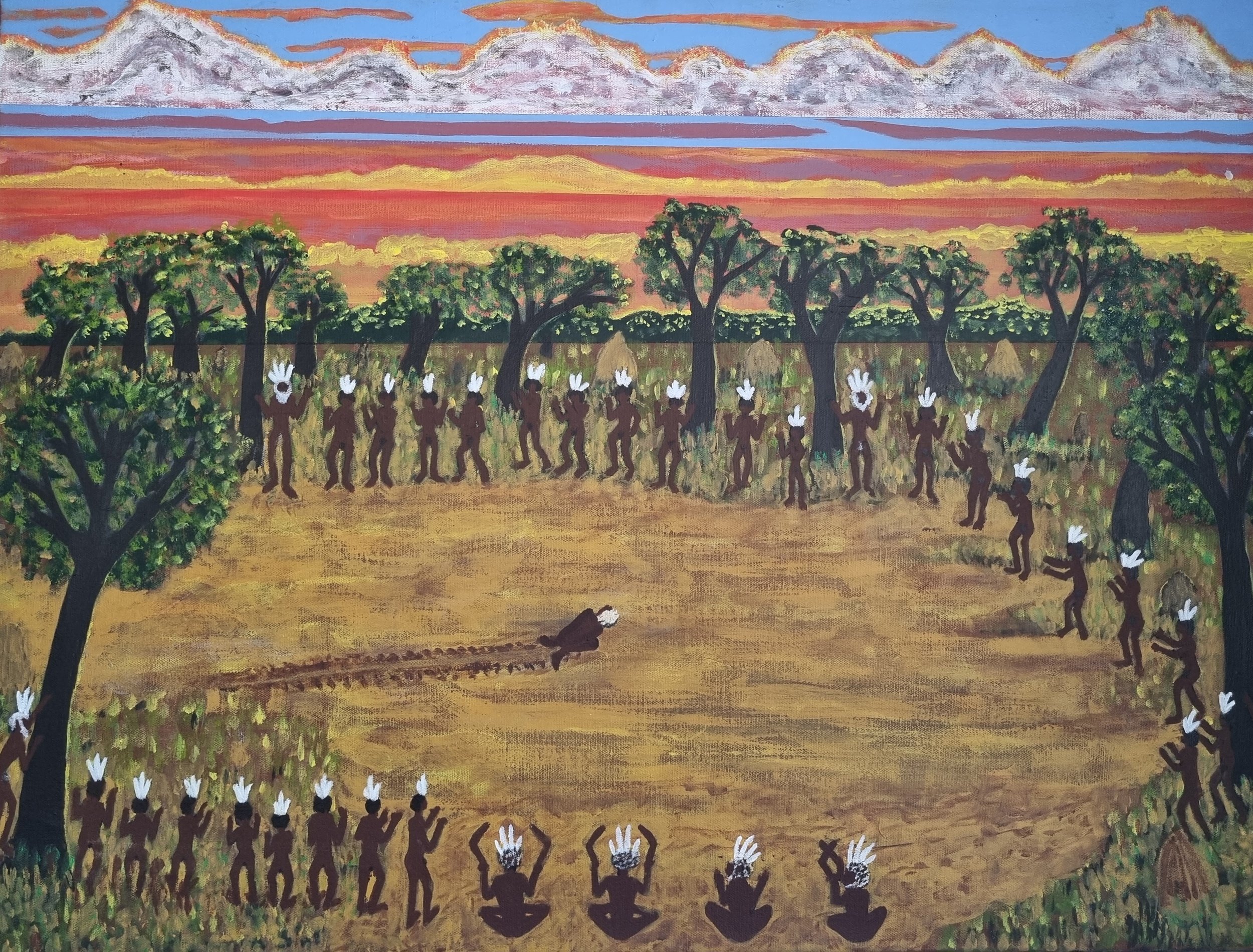

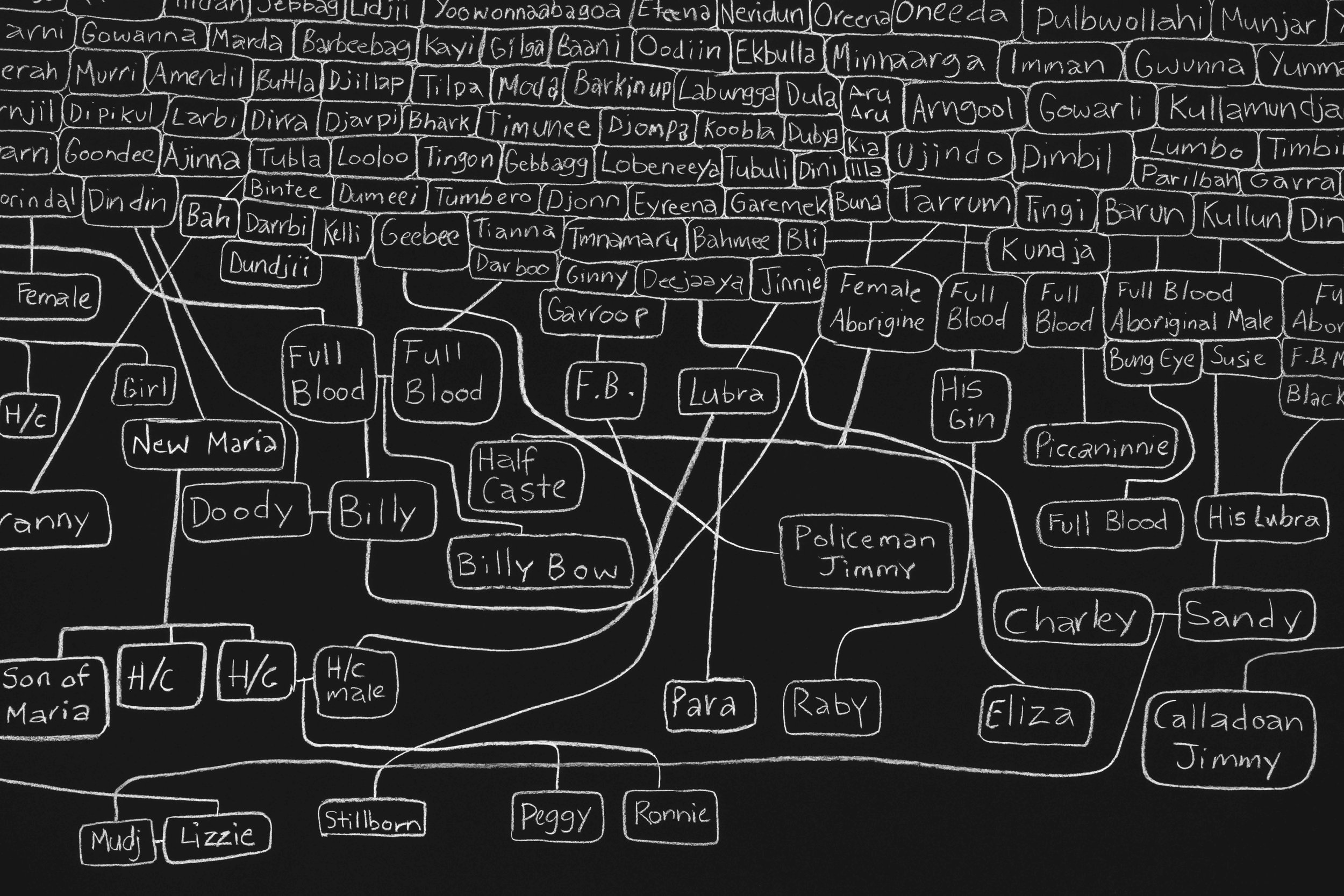

Embracing the space is Aunty Julie and Markeeta’s 75-metre-long mural of the southeastern coast as it would be seen from sea. Bold blue lines ebb and flow along the wide white walls, delineating sites of significance to those that can read Country. At points in this mural hang works by Yuin artist Mickey of Ulladulla (c. 1820-1891) whose drawings depict early colonisation from an Aboriginal perspective. The exhibition is a major showing of Mickey’s works, many of which are on loan from state and national institutions and finding themselves back home on Yuin Country for the first time. At the opening, Aunty Julie and Aunty Cheryl talked about their intention for the exhibition to be a a soft welcoming to culture and Country for the audience and a welcome home to Mickey and his works. His drawings showcase the enduring spirit of the Yuin peoples through depictions of events such as big corroboree and traditional hunting, as well as the bounty of beauty to be found in the diverse bird and fish life of the South Coast. Also, they allude to more sinister ongoings by colonists. They are an important look back in time—and a reminder of how far we have come collectively.

The adjacent space hosts Aunty Julie’s paintings and sculptural works. Her paintings depict cultural figures living on Country, their journeys and the stories and songs they carry. Each individual painting channels the story and spirit so naturally they seem almost ready to jump about the room themselves. Vibrant colours and cheeky sculptural elements—such as birds sitting outside the canvas frame—bring a liveliness to the museum space reminiscent of the Country outside the building. With her deliberate and bold lines, Aunty Julie stresses that the “South Coast style” of Indigenous mark making did not die with colonisation. It was merely sleeping in the landscape and in the stories. Her works are reminders of enduring presence and that the South Coast style continues to persist and evolve.

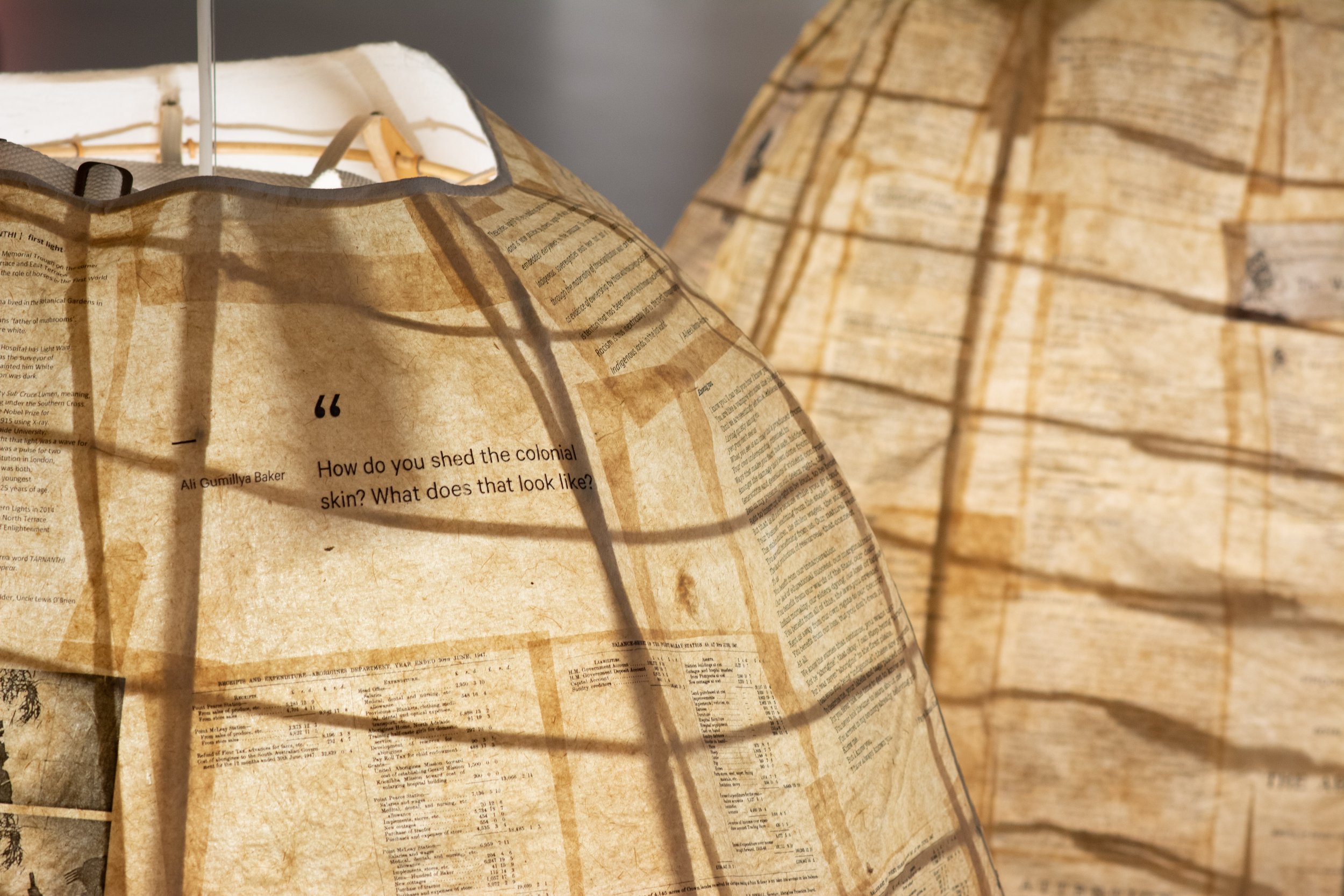

Aunty Cheryl’s textile works encapsulate the warmth of community. Wambarra Wurun (Black duck babies) (2024) sits opposite the entrance, depicting a Yuin family using yarn, cotton and recycled blankets. Around the corner stands Aunty Cheryl’s Dhawalanj bunbal-ba banggawu (Many trees and Burrawangs), a massive undertaking that demonstrates Aunty Cheryl’s proficiency in screen printing. This massive cloth installation pools at the bottom, the lapping undulations of the material mimicking the creeks that wind their way across Country. On the fabric sit oversized woven baskets burgeoning with models of bright orange Burrawang seeds, which sit ‘soaking’ against a backdrop of dense forest of tree and brush, fern and gully brimming with wildlife—all depicted through Aunty Cheryl’s style. The work touches on the tradition of Indigenous families leaching the toxins out of Burrawang seeds in rivers and creeks prior to processing them to make bread.

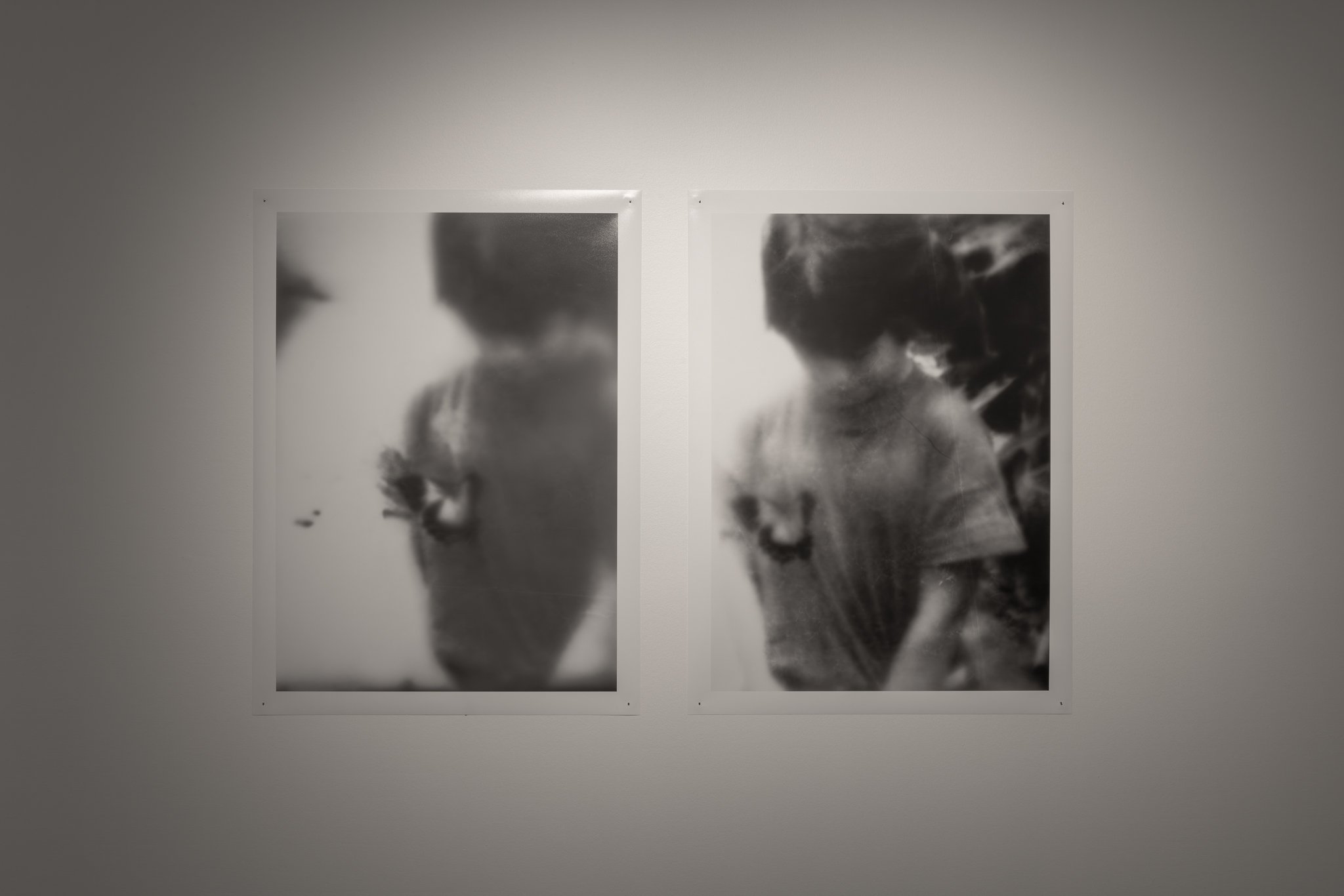

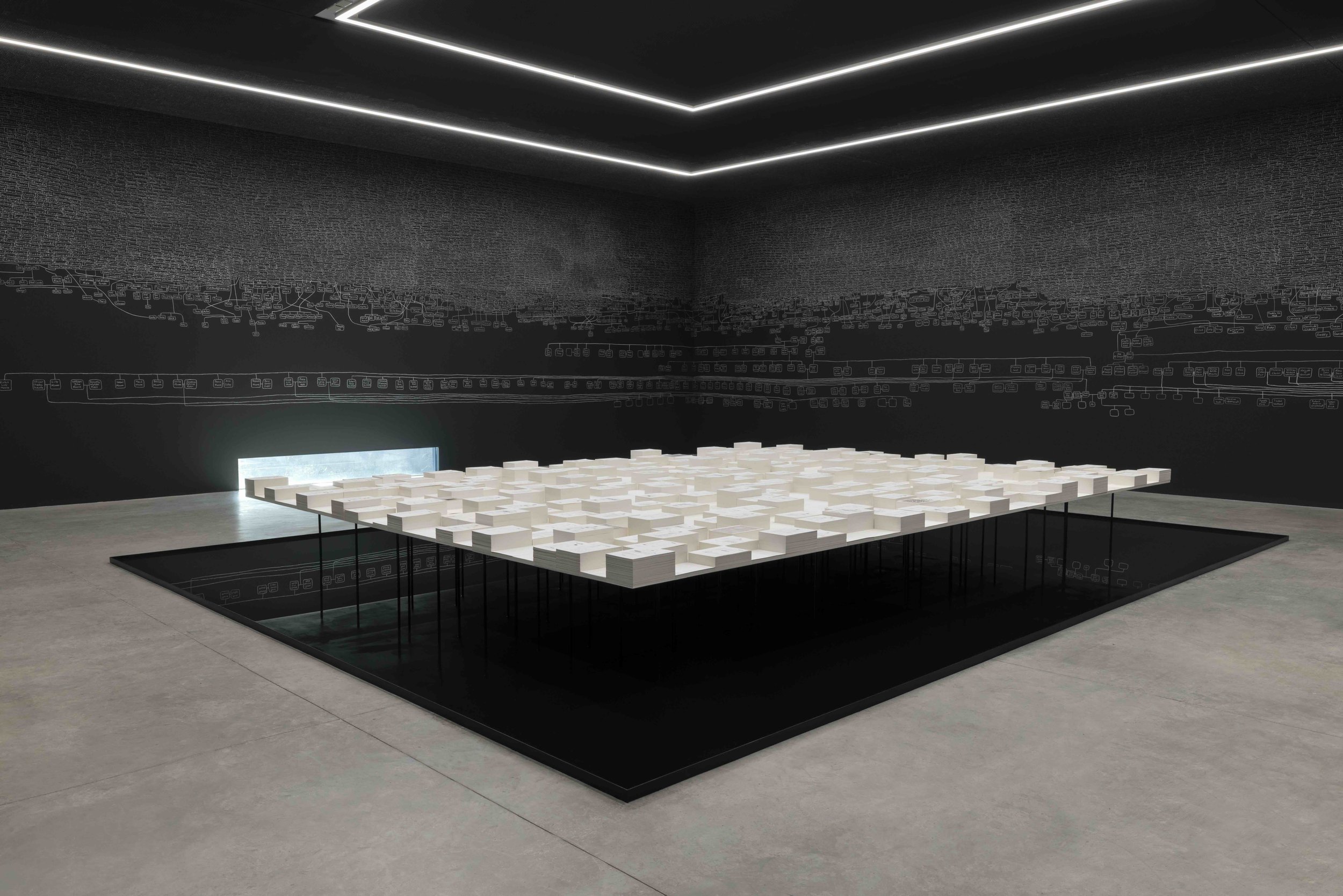

Throughout the exhibition, Jones challenges notions of place and Indigenous histories as they exist in relation to the institutional ‘gaze’, particularly how institutions—which can be extractive bodies—navigate their relationships with objects intrinsically tied to place. The turpentine trees of gunyah that uphold and dissect the main museum space were sourced from the surrounding bushland and were cut down with respect to—and in accordance with—Yuin knowledges and the bringing back of fire to Country. Backburning efforts prior to 2019 meant that the area was spared the worst of the 2019-2020 South Coast bushfires. The continued implementation of traditional Yuin knowledge by resident countryman Joel and his colleagues has allowed Bundanon to thrive not only as a cultural entity, but also as a sanctuary for a healthy and recovering ecosystem. There are sectioned spaces around Bundanon for Bob the resident brown snake to sun soak and open country for ’roos and wallabies to graze. Jones has created space for the continuation of traditional Yuin means of land management as well as bringing Country into the museum building, deconstructing and creating room for South Coast artists and the South Coast style to return.

Aunty Julie, Markeeta, Aunty Cheryl, Mickey of Ulladulla and Jones have created a sincere welcome to South Coast culture in ‘bagan bariwariganyan’. The exhibition calls us to recontextualise our relationship with Country and place—a place can be many things across many frames of time (or even all at once) but remains the same Country. It is a celebration of thousands of years of trade and exchange between neighbouring communities, it is a reminder of what was always here and it is a warm welcome home to ol’ mate Mickey of Ulladulla.

Tyson Frigo (Wiradjuri/Yuin)

‘bagan bariwariganyan: echoes of country’ is on at Bundanon until 9 February 2025