A spectrum of disgust, celebrated: Juan Davila at Foxy Production

/An alien in the colonial outpost, Juan Davila has sewn seeds of discontent via a discombobulating process of abject humour and history painting for five decades. A small selection of these works are on view at Foxy Production in Manhattan as part of Davila’s first solo exhibition in the United States.

The Santiago-born, Naarm/Melbourne-based painter is an idiosyncratic elder of critique. I like to think of his belated United States debut as one that coincides with the fading superpower’s festering empire, because Davila is a connoisseur of nation-bashing. Nation-bashing comes in many forms, one of which is creating the conditions that stimulate the slipperiness of interpretation, where confusion is a guiding force, freed of the colonial imagination by indecipherability.

There have been past attempts to censor Davila’s work, most notably from the Hayward Gallery in London in 1994 and the 4th Biennale of Sydney in 1982. If censorship is based on a culture’s fear of its own interpretation, how do these images, rooted in the subconscious and the poetic traversing of time, land outside the settler-state?

Davila straddles numerous modalities, from subtle gestures to blunt caricatures, in which humour can be seen as a call to consciousness, such as in Crocodile Dundee (1988). Is there anything as uncomfortably fun than a gay man depicting two of Australia’s most treasured heterosexual men engaging in sodomy at the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic? Elsewhere on the same plane of Crocodile Dundee is a naked Queen Elizabeth II, the original Bankcard logo, a pissing boy with a condom dangling from his mouth, a cartoon of a few cavorting crocodiles, and a small Parliament House in Canberra with a bent flagpole bearing the Union Jack. Placing Parliament House beside the Bankcard logo is one way of conflating the nation-state with big business (1988 was Australia’s Bicentenary). There is also a tiny clump of fingernail clippings and hairs, adhered with dollops of thick oil paint. To attempt to decode the symbols, appropriated moments, disorganised gender and sexuality and allusions to repression and oppression, is to submit to the burden of history. There is no escape, only voice and tone where viewers can open themselves to the vagueness of textures of discontent. A spectrum of disgust, celebrated.

Somewhere between 1988 and 2003 Davila shifted from bombastic compositions of ridicule to whimsical depictions of figures in the Australian landscape that cradled critique via references to art history. Davila is said to have disagreed with modernism impeding on figurative painting as a tool for political stimulation, and subsequently worked to rectify that interruption. Meandering through styles is a way of resisting the singular cohesion of modernism. This intention feels almost quaint amid the deluge of AI and the gentrification of our imagination.

Two women on the banks of the Yarra (2003) is a direct response to Gustave Courbet’s The Origin of the World (1866), reversing the gaze of the viewer over a pair of female figures and driven by a lack of reverence towards the way women have been depicted throughout art history. Perplexing is the insertion of two found portraits, collaged onto the painting, and sitting above the women. One is of an Indigenous man and the other is of a white man in smart casual attire holding a book. The women look upwards, towards the sky, and the men return the gaze of the viewer. While the title of the painting only refers to the two women, and the Yarra which is abstracted in the background, the inclusion of the male portraits reinforces references to nineteenth-century female objectification and the othering of Indigenous Australians through primitivism.

Naarm/Melbourne’s Yarra was once renowned as the world’s muddiest river. Since European settlement, land clearing and development have meant that a layer of silt is permanently suspended on its surface. So, to emulate nature’s response to duress is to muddy the waters. Much of the pleasure of such work is leaked through contradiction: the abstraction that surrounds the figures, who of course benefit from a kind of ocular supremacy, is as important as any centre of interest. The painterly brush marks at the edges of the canvas are an analogy for what exists at the borders of comprehension, in the often-misinterpreted edge lands of the Australian landscape.

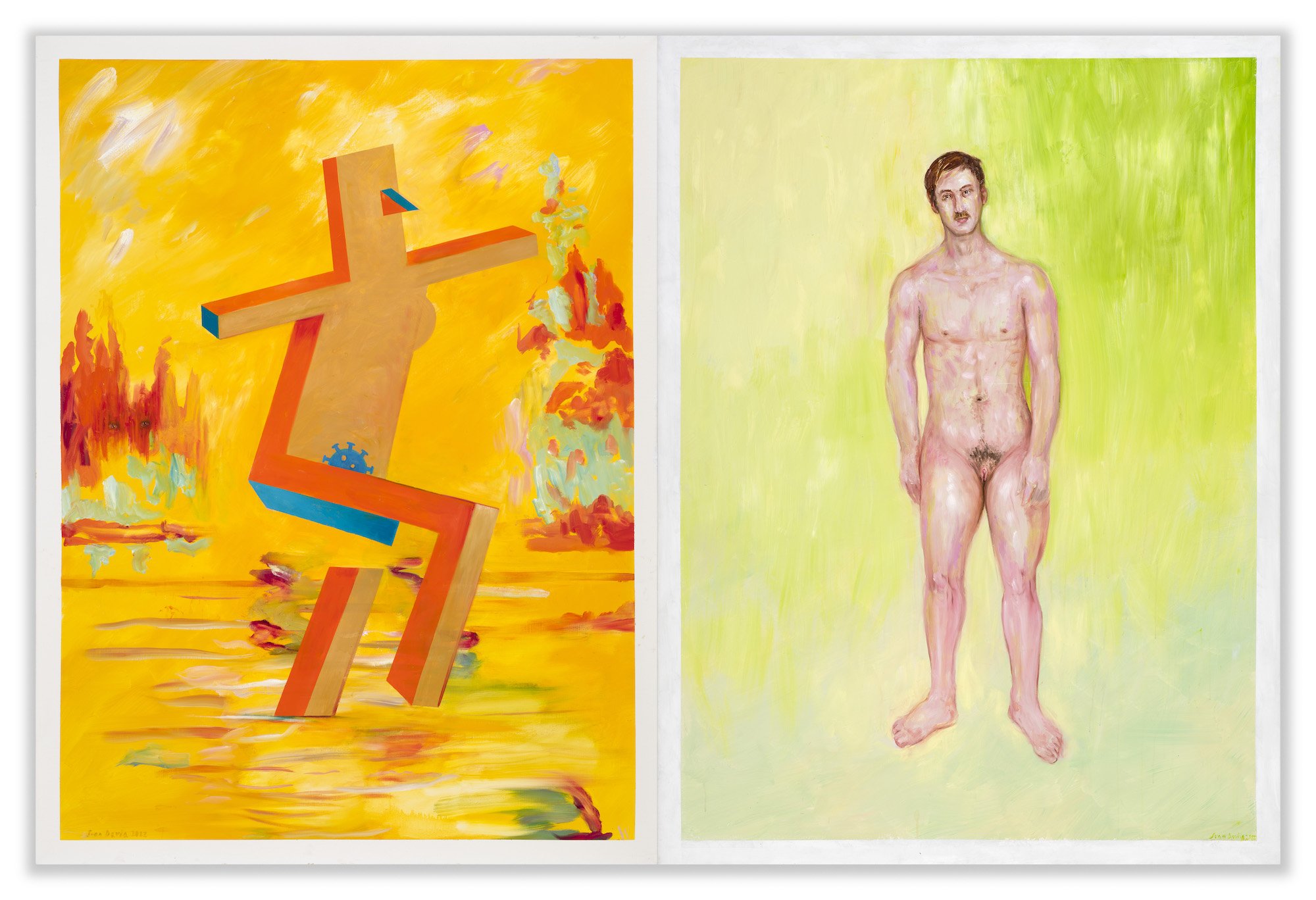

One of the most recent paintings, Untitled (2022), is much more economical. The diptych consists of a cubed figure with coronavirus-shaped genitalia stepping in an abstract yellowed landscape, next to a naked transmasculine person suspended in a lime-green background, staring blankly at the viewer, their withholding and simplicity bewitching.

To interpret Davila is to walk into the prison of one’s own conditioning, wading through the murky areas of subjective subconscious and the wild zones of the colonial imagination. His work resembles a directive but would never dare to tell us what to think. Instead, it socialises us with the anxieties, celebrations and shame of each era, stitching together elements of populism and the fringe, testing their compatibility. To wander through different times, styles and ideas is a way to avoid the singular narratives of nationhood or modernism. These works transcend their original indictments through their emphasis on the magic and the friction that occurs when someone punctures the horizon line, muddying the waters.

George Egerton-Warburton, New York City

Co-presented by Kalli Rolfe Contemporary Art, ‘Juan Davila’ is on display at Foxy Production in New York City until 25 June 2023.