Death and forever: Daniel Mudie Cunningham at Wollongong Art Gallery

/From a position on the left-hand side of the gallery space, the soft glow of a neon sign is reflected in reverse on the glass surface of an archival frame, momentarily obscuring a poster citing funeral songs.

I travelled from Warrang/Sydney to Woolyungah/Wollongong to see ‘Are You There?’, Daniel Mudie Cunningham’s first career survey. Tenderly curated by James Gatt, the exhibition spans three decades of Cunningham’s practice and evidences a lifetime of performance and documentation.

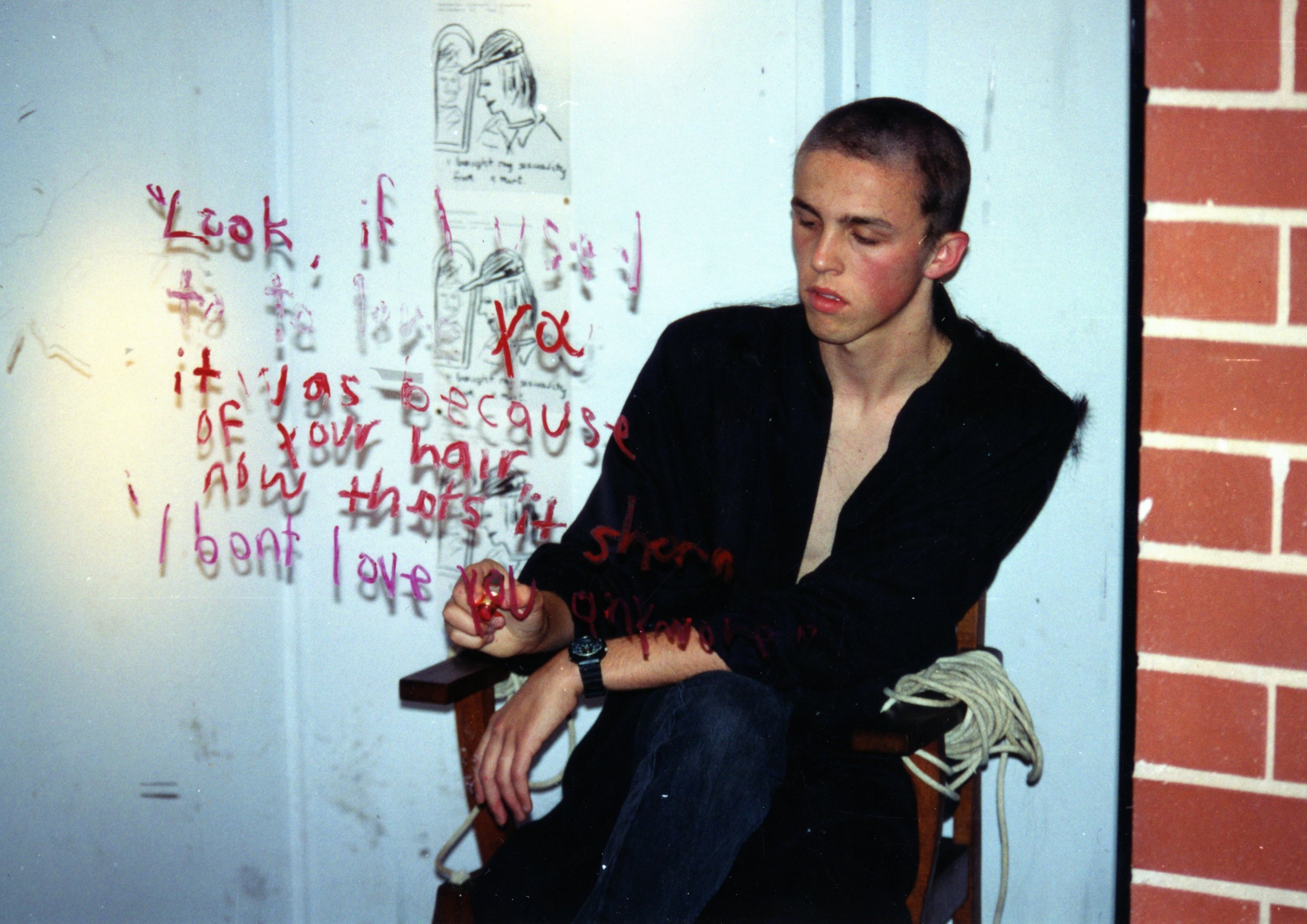

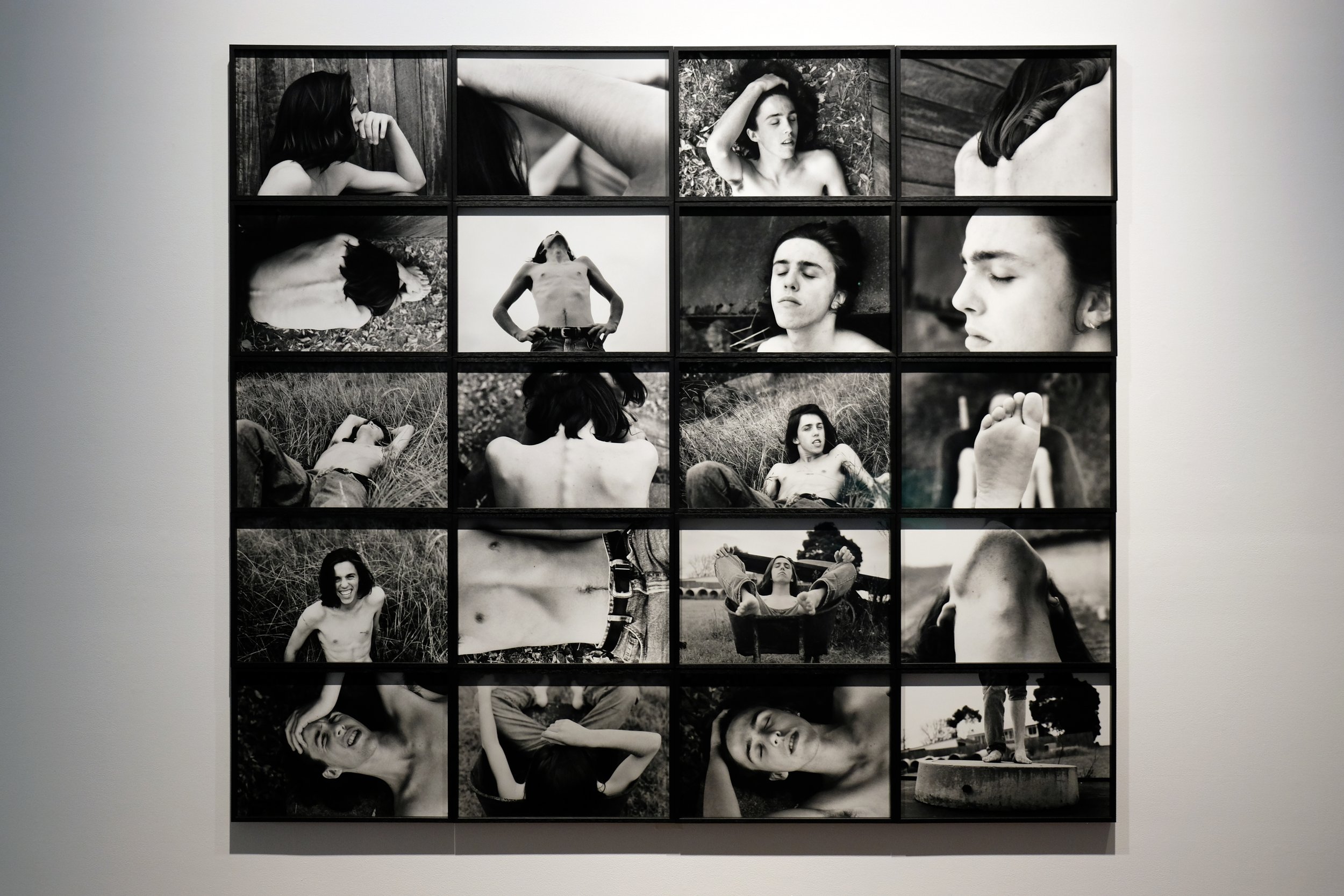

Informed by the dove-tailing experiences of growing up in a conservative religious household and as a gay man in the 1990s, Cunningham’s cyclical artistic gestures respond in part to the promises of eternal damnation and death. A family photograph of the artist's younger brother, buried to the neck in sand, conjures David Wonarowicz's self-portrait Untitled (Face in Dirt) (1991), and reads here as a reflection on mortality. In Lonesome Cowboy (1993) an 18-year-old Cunningham riffs on the homoerotic imagery of Andy Warhol’s Lonesome Cowboys (1968), marking the sensuous debut of his queerness via referential identification. In defiance of death and damnation, queer genealogies of art and the technologies of film and photography offer salvation.

Salvation can be reclaimed by eschewing heterosexual chronopolitics in favour of queer temporalities, including the aesthetic tropes of drag. ‘Are You There?’ is filled with anachronistic performance, lip-syncing, cheap wigs, and diva worship. In Licycle (1995), a flickering Cunningham performs as Liza Minnelli at the iconic cLUB bENT. In addition to Minnelli, Cunningham has appeared as intimations of Cyndi Lauper, Tina Turner, Bette Midler, and others throughout his career. In Gender is a Drag (1993/2013), a split screen shows Cunningham applying makeup, while also shaving his shoulder-length hair to the scalp, staging a kind of gender autopoiesis through the act of becoming and unbecoming.

Reenactment is critical to Cunningham’s oeuvre. In a nod to Nan Goldin, The Ballad of Technological Dependency (1998) comprises audio taken from the artist’s answering machine, set to a slideshow of friends in varying degrees of drag speaking on the phone. This approach is later revisited in Repeats (2000), in which Cunningham references iconic scenes in cinema history, including Pillow Talk (1959) and Scream (1956), employing the same answering machine and slide-show arrangement.

Drawing from a 1995 entry in Cunningham’s art school journal, On a Queer Day You Can See Forever (2023) could easily read as idealism, particularly at a time when the politics of queerness feel watered down in semantic satiation. Reimagined and rendered as a neon signage artwork 30 years into the artist’s career, the text reads instead as an ode to the unique insights and understandings of youth.

Cunningham’s threads of reenactment, self-documentation, diva worship and the spectres of death come together in his seminal work Proud Mary (2007, 2012, 2017, 2022). Now incorporating its fourth iteration, Proud Mary sees Cunningham perform a lip-sync to his own funeral song, Tina Turner’s titular 1971 cover of ‘Proud Mary’ by Creedence Clearwater Revival. Informed in part by the loss of Cunningham’s brother in 2001, Proud Mary sits beside a poster listing funeral songs, inviting reflection on the ways we remember the dead and the ways we anticipate ourselves being remembered. The iterations will continue until, of course, they stop. ‘Are You There?’ reminds us to forge our own visions of forever.

Blake Lawrence, Warrang/Sydney

Curated by James Gatt, ‘Are You There?’ continues at Wollongong Art Gallery until 10 September 2023.