Inside Archie Moore’s ‘kith and kin’—the exhibition that won the Golden Lion at the 60th Venice Biennale

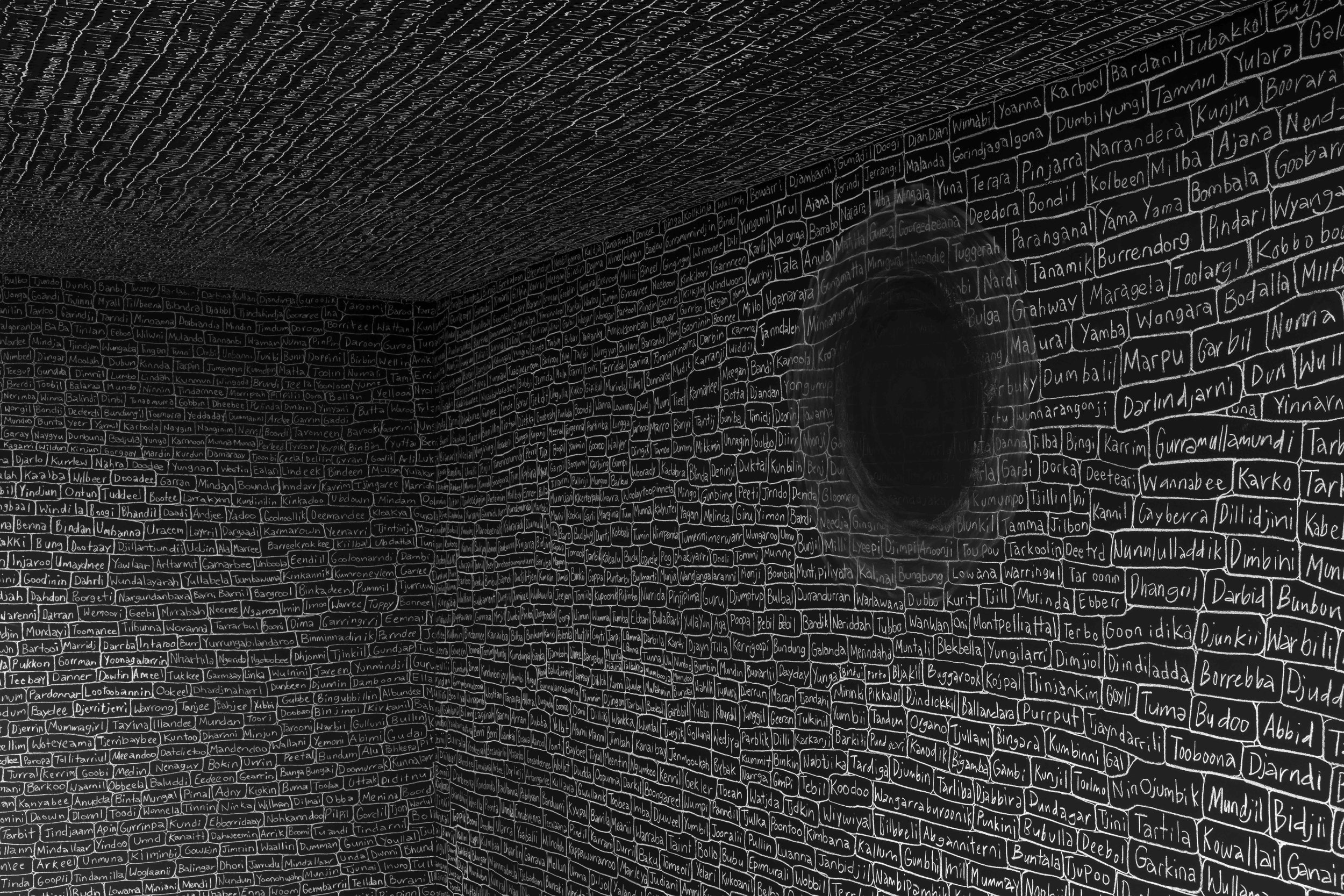

/I step into the dark, quiet space and find myself surrounded by thousands of Ancestors, their names written in white chalk on blackboard paint covering the walls and ceiling, all of them engulfing me in a giant family tree. The names look down on me like stars in the deep night sky.

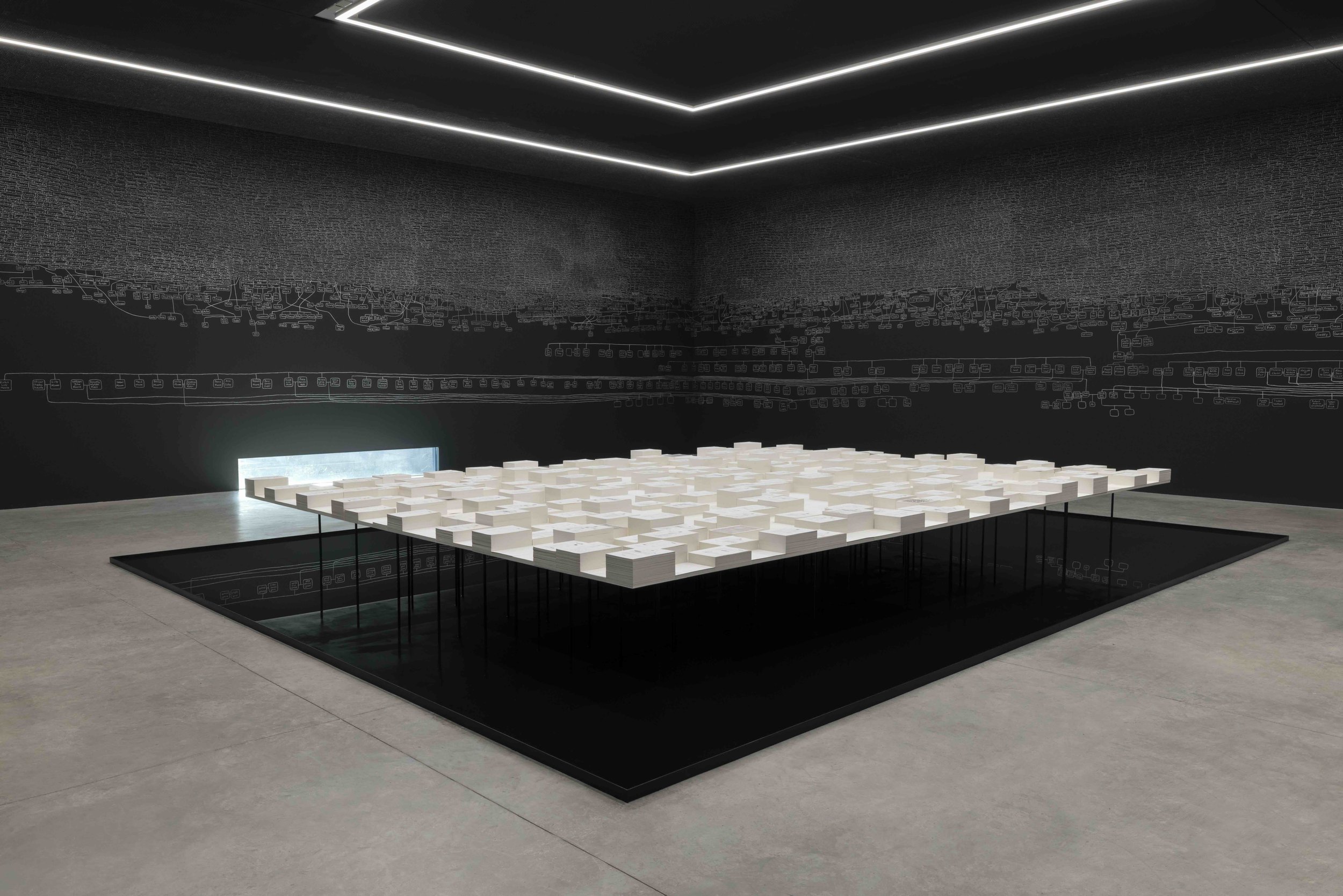

In front of me is what first looks like a model of the cityscape, but upon closer inspection is revealed to be piles of documents, reports of the deaths in custody of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia. I pause and look deep into the pool of reflection at the foot of this table of documents. I stand there and contemplate this immense exhibition, ‘kith and kin,’ by Kamilaroi and Bigambul artist Archie Moore, which has been curated by Ellie Buttrose for the Australia Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale.

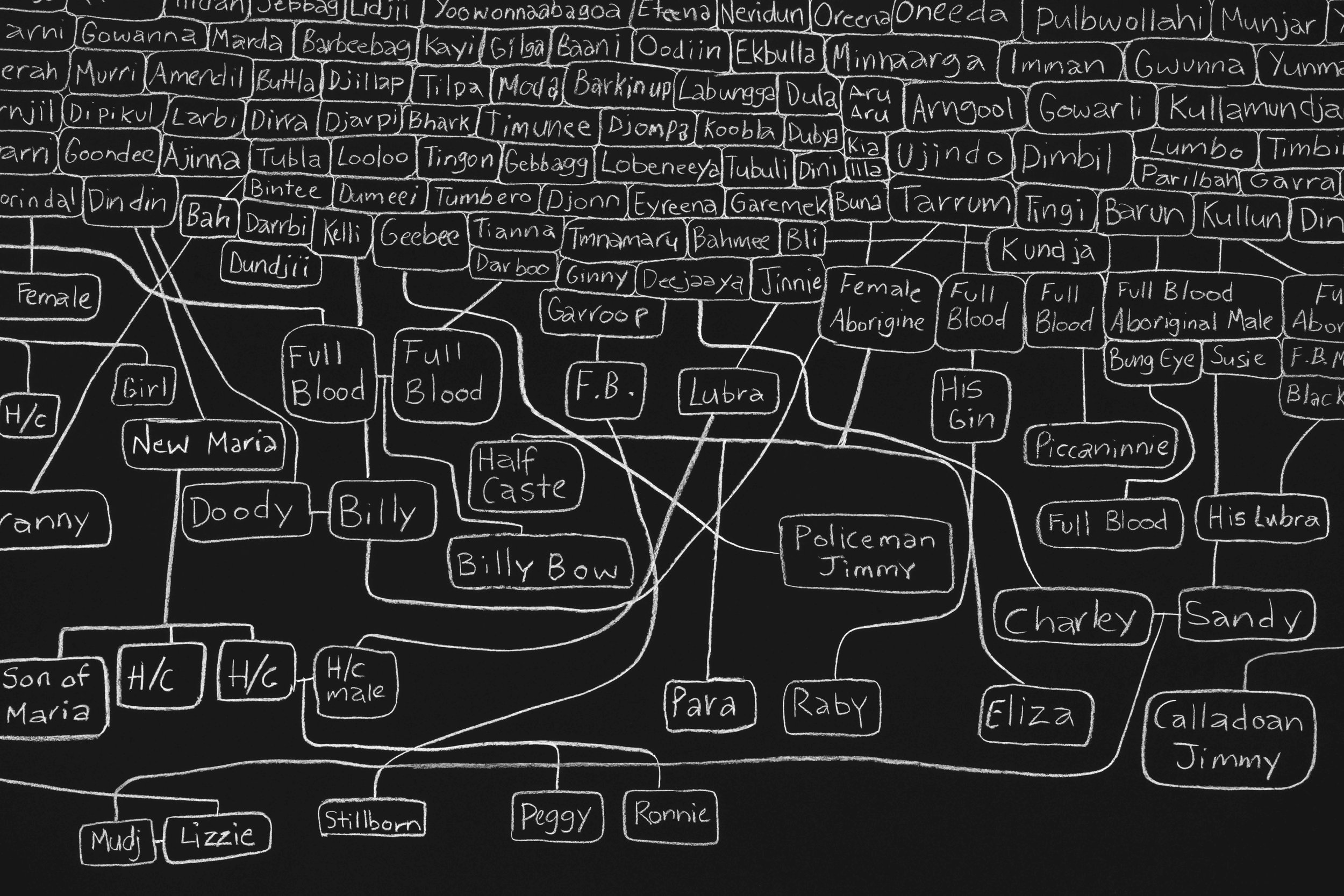

I walk around the walls, reading each name, tracing each connection. Nestled in this First Nations family tree, I find moments where missing people’s histories have been erased, the chalk rubbed out and faded, or deep black holes where no information exists at all. Some boxes feature crude names that were used in the past to incorrectly label and identify Indigenous people. I recognise one – ‘half-caste’ – a term that was placed upon me as a child, and one I firmly reject.

Some boxes are simply not filled – these people’s names are absent, yet their absence speaks loudly. I reach the centre of the room and the box marked “me.” The story of Archie begins here. On one side, there is the neatly arranged family tree of his father’s British and Scottish heritage. On the other, his mother’s Kamilaroi and Bigambul family forms a beautiful flowing current of names, lines and interconnected kinship relationships. This Indigenous family tree grows and spreads throughout the exhibition space, reaching the heights of the ceiling and fading into its dark abyss.

Evidence of Archie’s research into his genealogy is incredibly impressive. Through his years of investigation, he has accumulated more information than many institutions hold. I tried to imagine Archie’s journey with this work, from obtaining information about his maternal great-grandmother, Jane Clevin, from the anthropologist Norman Tindale, to venturing into the depths of state and federal archives. The journey to obtain the information and also to hold it, in his heart and spirit, must have been incredibly heavy.

My gaze falls from the dark ceiling down to the bright white piles of documents, some stamped with the seal of the crown, many of which feature ‘just’ another name on a piece of paper, another Indigenous death in custody, another family member lost – an all too familiar story for First Nations people. The documents hover above the dark pool of reflection. It is as though they sit above the tears of all those families and Ancestors that surround me. Some of the names are from my community. I feel a deep sense of loss.

As I mourn, sparkles of light catch my eye. They dance on the walls through a small, floor-level window that lets the sparkling reflection from the waters of Venetian canals in, connecting this sacred space to the waters outside, and onwards to the waters of home. I find comfort that those waters are reflected in this space. I feel hopeful that through the power of art and Archie’s remarkable work, our stories are now being shared beyond Australia, and are connecting us with other Indigenous peoples around the world.

This is my second visit to the space. The first was jarring because I entered during the launch of the exhibition. It was filled with people yarning and laughing, doing what we have come to expect from an exhibition opening. However, this was not your typical exhibition. I stood at the top of the display, solemn as I considered the juxtaposition of the endless names of Indigenous people who have died, set against the packed space of people celebrating. It did not feel right to me. However, that is the machinery of an exhibition launch. I understand why these events happen – and there was much to celebrate.

What is evident throughout the exhibition is the collaborative nature in which the work was brought together, with the support of Elder Bandjalung creative Djon Mundine; the considered exhibition design of Kaurareg and Meriam architect Kevin O’Brien; and the backing of Creative Australia, which commissioned the work. Ellie, from the Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art, has curated the exhibition with care and sensitivity. The complementary and collaborative nature of these relationships manifest themselves in this exceptionally thoughtful, heart-swelling exhibition.

‘kith and kin’ won the biennale’s prestigious Golden Lion award for Best National Participation. This is the first time in history an Australian artist has received this accolade. Congratulations to Archie, Ellie and the Creative Australia team on this deeply moving exhibition.

Peggy Kasabad Lane (Saibai Koedal Awagadhalayg), Venice

Peggy Kasabad Lane is the First Nations Curator at Court House Gallery and Tanks Arts Centre, Cairns, and attended the Venice Biennale as part of the (re)situateBiennale Delegates program run by Creative Australia.

Curated by Ellie Buttrose, ‘kith and kin’ by Archie Moore continues at the Australia Pavilion, Venice until 24 November 2024.