Crushed by waves: Reuben Holt in conversation with Marco Fusinato

/Marco Fusinato is an artist whose practice moves between performance and installation, photography and recording. Last weekend he premiered a live version of his ongoing project DESASTRES at Atonal, Berlin’s annual festival for sonic and visual art in a former thermal power station. Taking place within the venue’s 100-metre-long turbine hall, it’s an evolution of the monumental work Fusinato presented over 200 days at the Venice Biennale’s Australian Pavilion in 2022.

Reuben Holt (RH): How would you describe your work to someone who's never experienced it before?

Marco Fusinato (MF): I work as a contemporary artist and a noise musician, as an artist I work across a range of projects. Each project may be different but there's a sensibility that runs across all of them. Many of them focus on my interests around the tensions in opposing forces, for example, the underground versus the institution, noise versus silence, minimalism versus maximalism, purity versus contamination and so on. As a musician I use the electric guitar and mass amplification to create a physical experience for the audience.

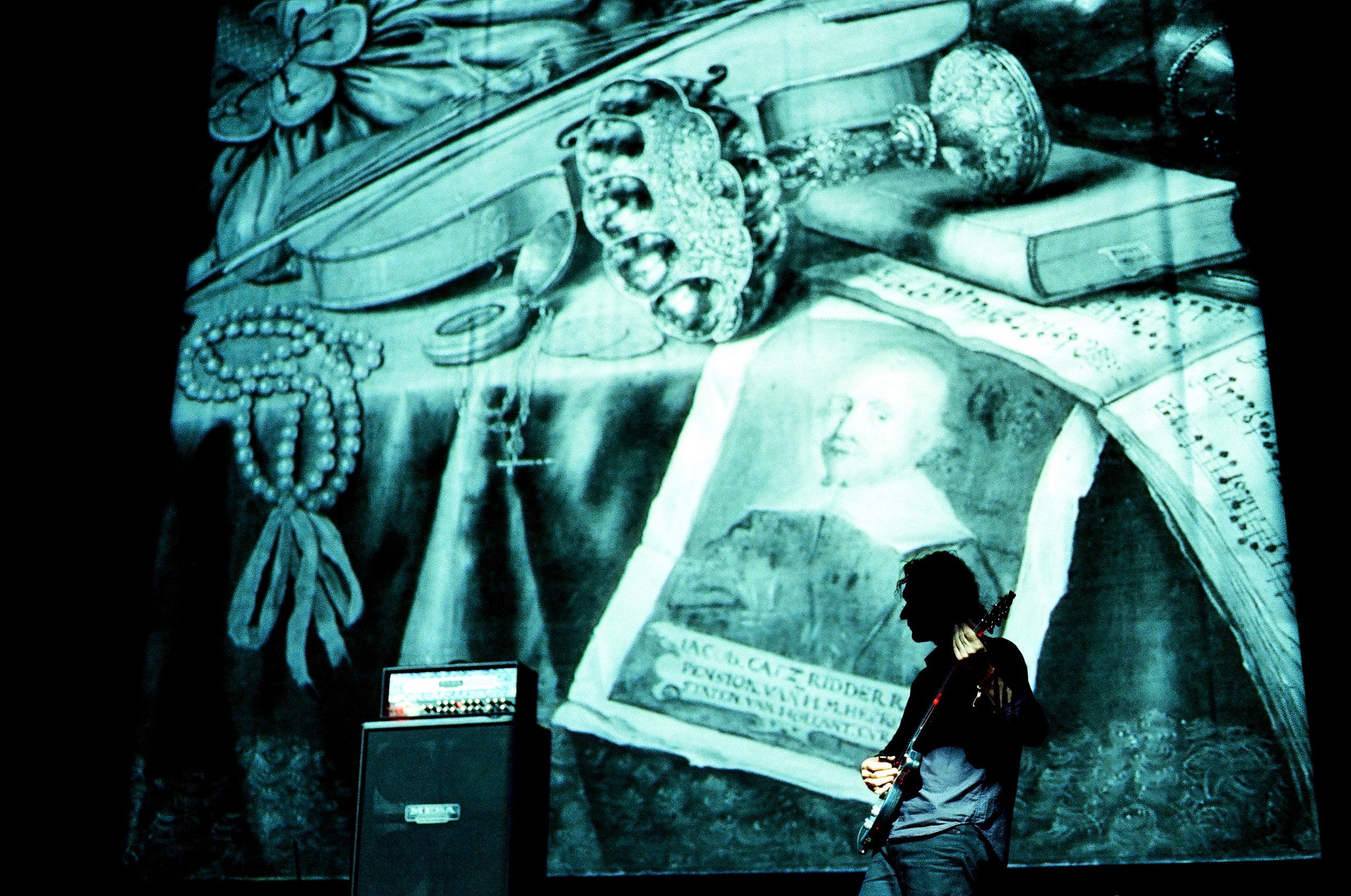

DESASTRES is a culmination of many of my interests and previous projects - from noise improvisation, drone, down-tuned ‘corrupted’ chord progressions through to mass image archiving. DESASTRES uses the force of the sound and the power of the images to create impact on the audience - whether it's in the gallery or a festival situation.

RH: Marathon guitar performances have been a recurring feature in your work, from the Spectral Arrows series staged in various galleries around the world, to the 200 days of eight hour guitar sets at the Venice Biennale. What aesthetic role do they play?

MF: There’s a big difference exhibiting in a gallery compared to performing improvised music. The main one being time. An exhibition can last weeks, months, years, whereas a performance in a club or festival is usually under an hour. Over a decade ago I became frustrated with touring (travel time, hotels, transfers, waiting at the venue), only to be on stage for under an hour. Spectral Arrows began out of this frustration. I thought, well if I’m going to turn up, I’m going to stay all day. I perform for the entire opening hours of the space (gallery, museum, theatre, venue) which is usually between six to eight hours. It’s an occupation, a job. I set up facing the wall with a line of amplifiers facing out into the space. I have my back to the audience, so I’m not distracted by who is in the room. It allows me to concentrate on the sound and removes any desire to ‘entertain’. I let the physicality of the sound take me in directions that are unexpected. I’m constantly soaked in an overload of harmonics and clashing frequencies. I lose sense of time. It's like standing in the ocean all day being crushed by waves. The audience is free to experience the work from anywhere in the space, for as long as they want, although it’s impossible to grasp the whole due to the duration of the performance.

RH: What kind of impact is audience behaviour having on the evolution of your work?

MF: In Venice (at the Biennale) I could feel them. On average there were around two thousand people every day, on some days 5,000 – that’s around 400,000 in total. The installation comprised three elements - me, the amplification, and an LED screen. These elements are usually on the stage but now the audience is in amongst it all, they are active participants which leads to all sorts of unexpected encounters and friction. People wanted to engage, and express their opinions. At times that would affect what I would do, for example if it got too much for me, I’d clear the room with the harshest noise I could make. Berlin Atonal was more like a traditional concert setup, with a large stage, PA system and massive video projection screen. A separation from the audience.

RH: In DESASTRES, your guitar is connected to an interface that allows you to manipulate the duration of images projected on the video screen. But not necessarily the order or content of the images themselves. What is the significance of chance in your work?

MF: For DESASTRES the sound is always improvised, and the images are randomized. I never know what image will appear on the screen. The control unit decides whether to bring up an image as I've chosen it - or it can choose to bring an image up in negative, cropped, or as a double exposure. It’s a constant surprise for me to see what image comes up next. The chance element confuses meaning, what one person makes of a series of images is different to the person standing next to them. There are many ways to interpret the performance. Keep in mind it is difficult to have a conversation while the images are cascading due to the volume so it’s fascinating to hear what sounds and images stayed with people.

RH: My understanding is that you collected most of the images during the Melbourne COVID lockdowns and yet some of them seem prescient of political events that were yet to unfold, for example, the war in Ukraine. I wondered what impact unfolding political events have on the evolution of the work.

MF: The images I select are very particular as they must be open enough for multiple interpretations by a wide number of people with diverse backgrounds. I want the images to have resonance no matter where the work is experienced. For example, when I choose images of conflict, they tend to be cropped in a way that doesn’t specifically show the location. So, whether it’s an image from art history or the war in Ukraine there’s a consistency.

I don’t choose images of politicians, celebrities, and so on. I try to eliminate the personality. I went through a phase of photographing newsreaders’ ties and what their hands were doing. They look the same the world over. That kind of stuff is more interesting to me.

DESASTRES relies on hallucinations in disorientation and an exhaustion from confusion.