Border anxiety: The 12th Gwangju Biennale

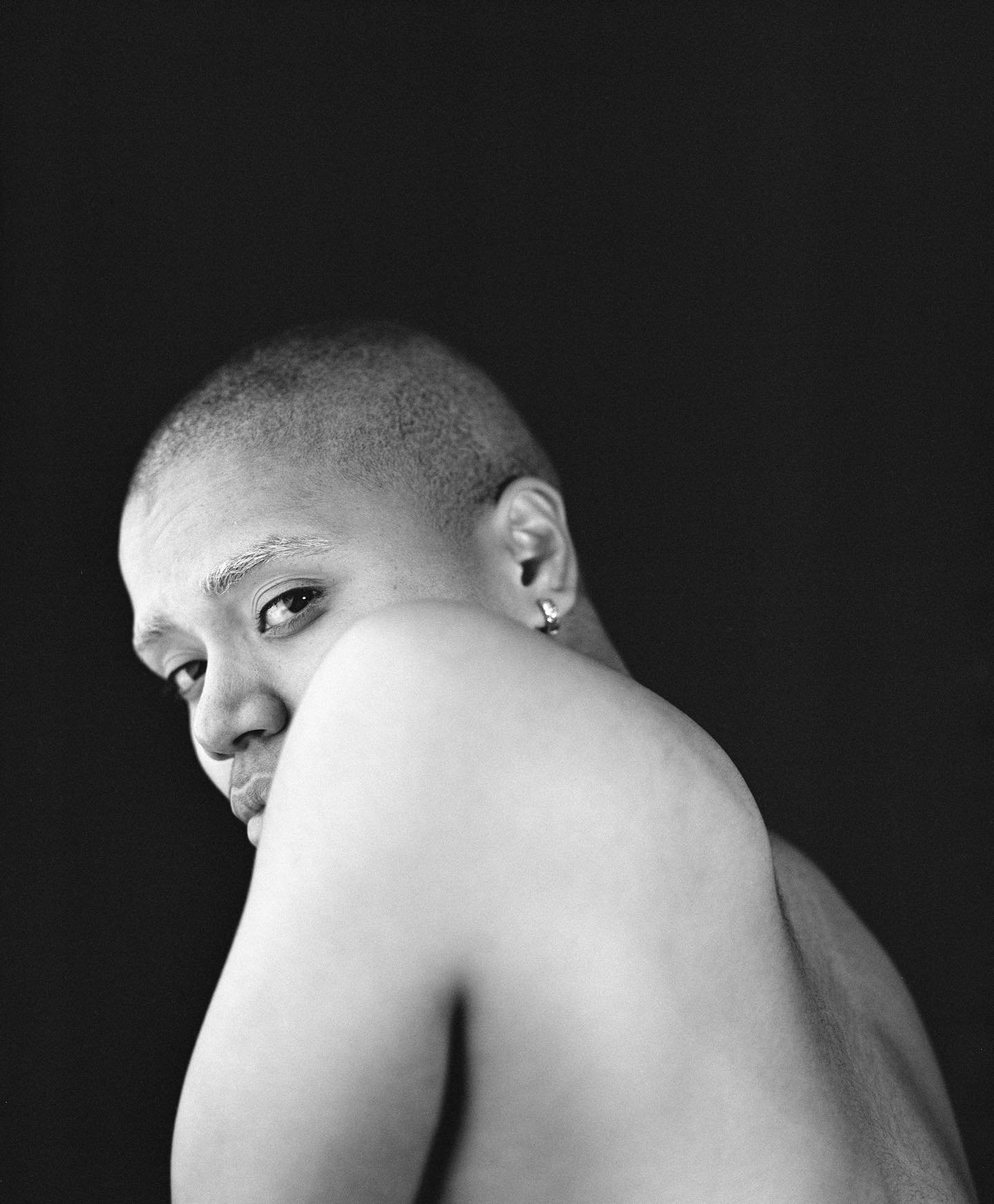

/Chen Wei, New City/History of Enchantment – Tunnel, 2010–18, mixed-media installation: neon lights, inkjet prints, light box, LED display module, prints, dimensions variable; image courtesy the artist and ShanghART Gallery, Beijing, Singapore and Shanghai

With around 236 biennales held around the world, there are few perennial exhibitions that carry the same global resonance and clout as South Korea’s Gwangju Biennale. For its recent twelfth edition (which ran from 7 September until 11 November 2018), the biennale abandoned the traditional single artistic director model and, instead, wove together the contributions of 11 local and international curators across seven exhibitions and four site-specific commissions and 153 artists.

This edition’s theme, ‘Imagined Borders’, drew on political scientist Benedict Anderson’s 1983 book Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, and also alluded to the inaugural 1995 Gwangju Biennale ‘Beyond the Borders’. With South Korea’s own recent political turmoil surrounding former president Park Geun-hye’s arrest, Anderson’s ideas of how communities form and interact with systems of capitalism, the media and opposing communities – along with an appreciation of the biennale’s own 23-year history – served as an intriguing open proposition.

Within the Biennale Exhibition Hall, the curators each empowered a selection of artists who imparted nuance to global news and national narratives. Curator Clara Kim’s ‘Imagined Nations/Modern Utopias’ conjured a cohesive exposition of nation-building through the optics of modernist architecture in her striking exhibition. A highlight was Tanya Goel’s Carbon (frequencies on x-y axis) (2017), in which the artist reconfigured building remnants from her native New Delhi into a mud-map that portrays the city’s rapid urbanisation.

Gridthiya Gaweewong’s exhibition of 50-plus screens explored notions of migration and geopolitics focusing on Southeast Asia. Drawing on veterans including Agnieszka Kalinowska, Dinh Q. Lê and Ho Tzu Nyen, she presented a successive string of short films that collapsed fact into fiction to create haunting enquiries into the multiple registers in which borders operate.

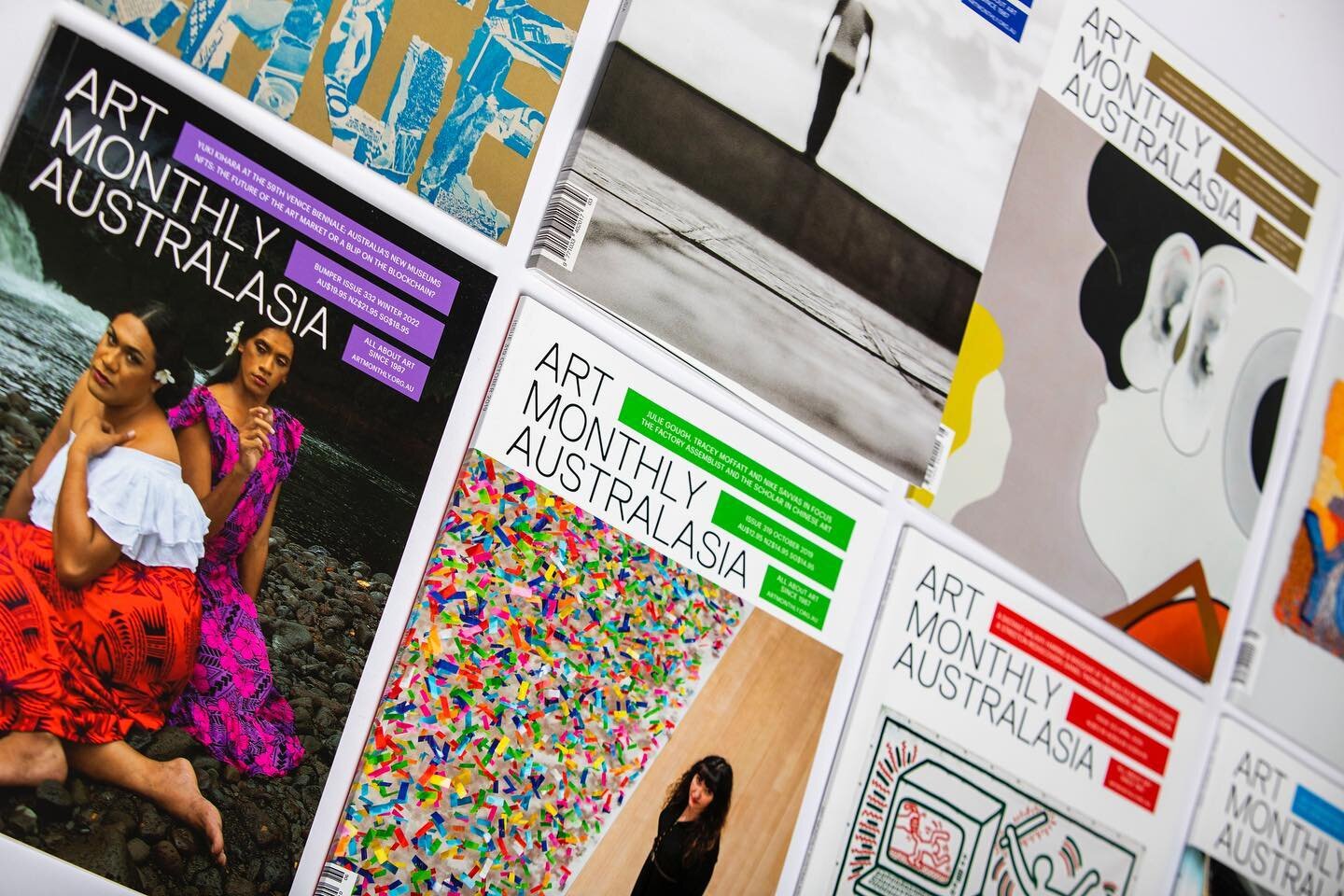

David Teh’s Gwangju Biennale history archive/anti-archive project ‘Returns’ memorably collaged together a series of performances and artist interventions, including those by Australians Brian Fuata, Agatha Gothe-Snape and Tom Nicholson, into a ‘walk-in magazine’ that posed questions about biennales, contemporary art and the history of Gwangju itself.

As with many biennales, the curators of the Asia Cultural Center venue were occasionally guilty of overreaching in their determination to shoehorn ideas, geographies and aesthetics into the biennale’s thematic. Good artists operate on multiple registers and this does not necessarily lend itself to a specific curatorial framework. Nevertheless, glorious moments could be found. For instance, Chen Wei’s New City/History of Enchantment – Tunnel (2010–18) offered a large tableau of neon-lit evening streetscapes of the burgeoning Chinese nightclub culture, drawing commentary on accepted social practices and changing realities for China’s youth.

Despite these occasional moments of disparate exhibition-making, ‘Imagined Borders’ was rich with determined globalism. Each exhibition served as a paragraph in a larger polemic that spoke to the porous borders of democracy and what this means – and more importantly – what this can mean in our increasingly Balkanised age. In the current context of vertiginous political, social, economic and artistic change, the opportunity to explore this proposition was alone worth the visit.

Micheal Do, Gwangju