Connecting threads: ‘So Fine’ at the National Portrait Gallery

/Nusra Latif Qureshi, Refined Portraits of Desire, 2018, watercolour, gouache, cotton, polyester thread, acrylic on illustration boards, 180 x 430cm; image courtesy the artist and Sutton Gallery, Melbourne

With a blockbuster media strategy and an opening speech by SBS journalist Jenny Brockie citing Linda Nochlin’s 1971 essay ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’, the exhibition ‘So Fine’ launched itself as a firm feminist statement about quality contemporary art made by women. It was conceived and nourished as a chance to explore, reinterpret and re-examine historical portraiture through a female lens. Nicola Dickson, one of the ten invited artists, says that she has never been so supported, emotionally and materially, by a curatorial process. National Portrait Gallery (NPG) curators Sarah Engledow and Christine Clark selected a culturally diverse group of practitioners, many of whom use processes traditionally concerned with women’s work such as china painting, tapestry, basketry, sewing, paper-cutting and drawing. These processes and more are used as paths into storytelling, the connective tissue of this robust exhibition.

Some of the stories are the artists’ own: Bigambul woman Leah King-Smith works digitally with her father’s photographs and her sister’s family history research to share with us her mother, Pearl King, as an ‘animated spirit being’. She works with different filters and lenses, fully cognisant of these double meanings and dubs her process ‘photography dreaming’.[i] She speaks of her work in textile terms: weaving fabric, threading interconnection. Senior Gija artist Shirley Purdie paints her family stories, some passed down to her and others from her own memories. They are all stories about women, and women’s traditional knowledge about food, dance, animals and country. Valerie Kirk dives into her own story of migration from Scotland to Australia, exploring the physical and psychological shifts as she continues to move between the two countries, weaving her shadowed selves into her handwoven tapestries. She weaves other objects into her meditation: Ayrshire needlework-painted slate roof ‘peggies’ and the actual needlework presented on fine muslin and cotton lawn christening gowns, the latter arranged cunningly by the curators like female colonial garb next to Purdie’s paintings of post-invasion camp life.

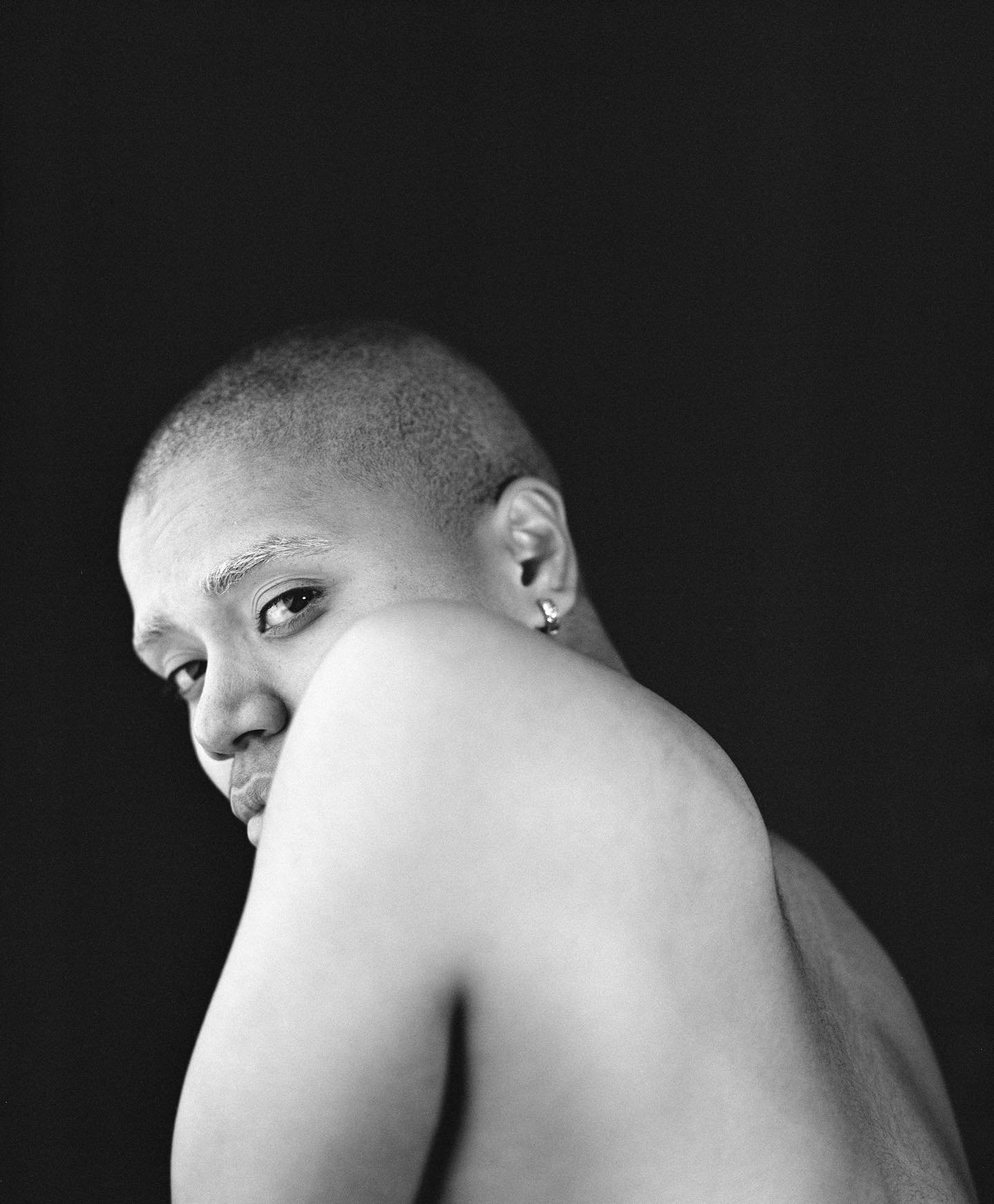

Other artists entwine their personal connections with found stories: while Linde Ivimey celebrates the work of Antarctic scientists by reimagining them as the creatures they research – lavishly magical – she also places herself and her friend within the scene as witnesses, although Ivemey’s own avatar looks downwards, absorbed in acts of meta-creation. Wathaurung woman Carol McGregor’s family possum-skin cloak (black seeds, 2016) links her generations to a wider practice of mapping land and ‘unsilencing’ stories through objects. Her series of small furred vessels pull us close while her title pushes back (Blood rape, 2017), and she ties a dark thread to Meret Oppenheim’s inviting Le Déjeuner en fourrure (1936). Red threads tie imagination and longing in Nusra Latif Qureshi’s installation Refined Portraits of Desire (2018), reworking century-old unnamed studio photographs and connecting them with contemporary emotional possibilities.

And then there is pure historicism, new slantwise looks at cultural touchstones: Fiona McMonagle’s haunting halftones of children from the British child migration scheme, the calico amplification of their cheerful smiles rendering them more as wartime wounded; and Pamela See’s 2017 series ‘Making Chinese Shadows’, which re-presents stories of Chinese settlers with delicate paper-cut silhouettes, offering a reminder that the Chinese have been settled in Australia almost from the start, and in some areas of Australia, outnumbering Europeans by ten to one. Nicola Dickson hones in on eighteenth-century French exploration of the South Seas, using sensory bombardment to evoke a sense of strangeness and affect. She attempts to return agency to Indigenous individuals by uniting separate contemporary depictions of landscape and figure. And finally, Bern Emmerichs’s three ‘quilted’ ceramic artworks, bursting with historical facts about convict women deported to Tasmania, with each woman named and many of them portrayed with every distinguishing feature listed in their records.

‘So Fine’ is aptly named: there is a joyful seriousness in the crafting of each work, an attention to detail that rewards both eye and mind. This lively, moving exhibition was planned to coincide with the NPG’s twentieth anniversary, and continues to progress the agenda of expanding and extending outwards from the gold-framed concretisation of male achievement. Brockie’s citation of Nochlin was a hat tip to the gallery’s efforts, and a timely reminder that there is always more work to be done.

‘So Fine: Contemporary women artists make Australian history’ is currently on display at the National Portrait Gallery, Canberra, until 1 October 2018; Caren Florance has been a 2018 Critic-in-Residence at ANCA, Canberra, in a special project partnership with Art Monthly Australasia.

[i] See Leah King-Smith’s online artist statement for ‘So Fine’: www.portrait.gov.au/content/so-fine-leah-king-smith, accessed 2 August 2018.

Article by Caren Florance from Art Monthly’s September 2018 issue 310. Purchase the September issue at http://www.artmonthly.org.au/single-issue-purchase