Gestures of the possible?: Kimsooja’s ‘Zone of Nowhere’ at PICA

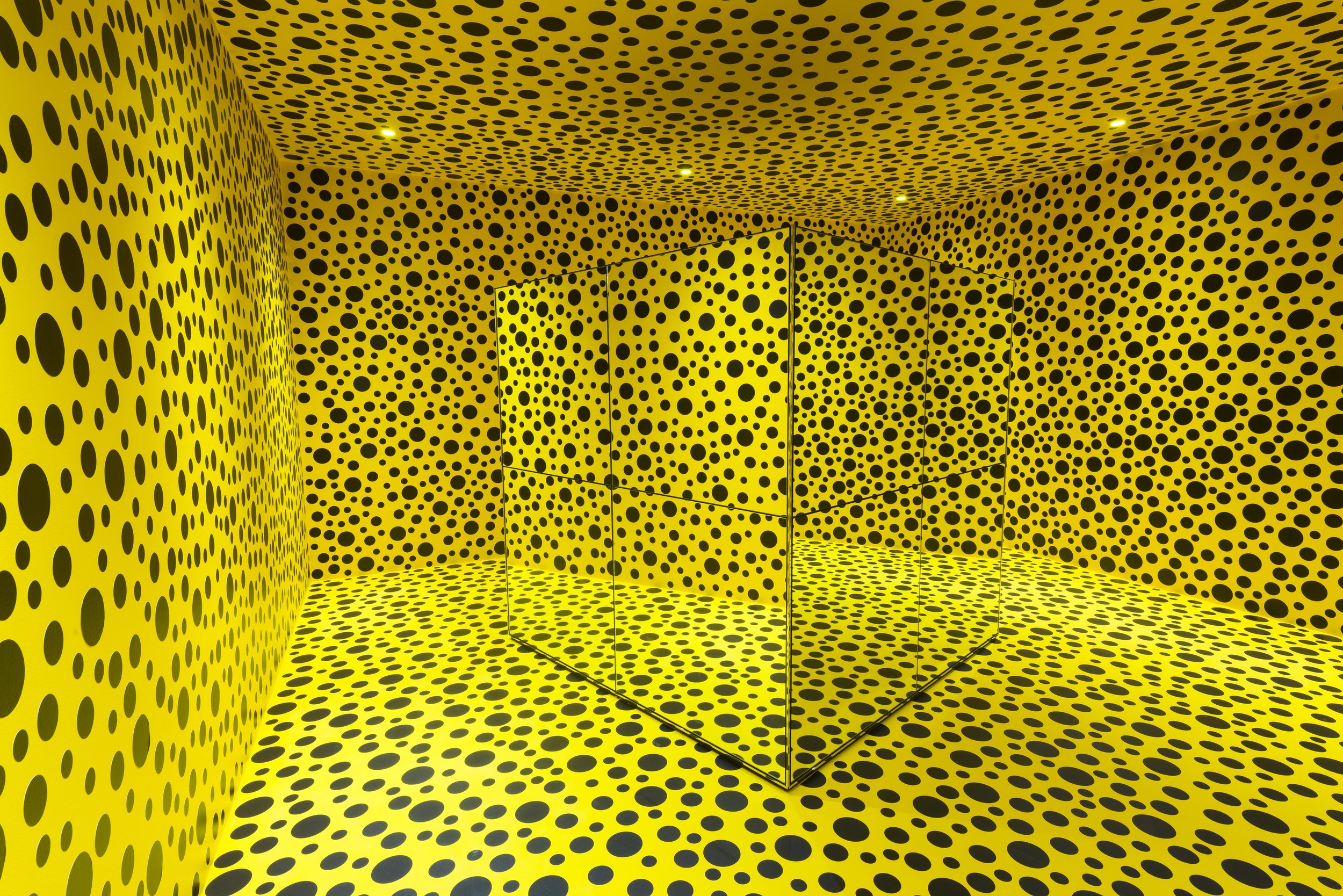

/Kimsooja, To Breathe – Zone of Nowhere and Bottari, 2018; installation detail view, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (PICA), 2018; site-specific installation; image courtesy PICA, Perth; photo: Alessandro Bianchetti

In the shadow of fluttering flags, there is a prevailing stillness about Kimsooja’s first Australian solo exhibition ‘Zone of Nowhere’, at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (PICA) and on until 29 April.

Thirty flags hang above the viewer in the main gallery, but unlike the flags we are familiar with, each is a transparency of itself combined with two others. This is the installation version of a video made for the 2012 London Olympics where, ordering the countries in alphabetical order, each flag coexists with the next. Extending her focus that pivots around cultural practices and symbolism of textiles – particularly the Korean bottari, fabric used to gather belongings into bundles for travel – Kimsooja’s utopian flags are precisely positioned in order to set the tone for the show.

In the current state of political, social and moral oversaturation, this exhibition is a moment of calm, a pairing back, a reducing of information, politics and social mores to their ontological basics. Why can’t these simple acts (the flags), rather than seeming like a utopian drag, and certainly not always aesthetically appealing, be the gestures of the possible?

Both floors of the gallery are sparsely but strategically dotted with such gestures. Bottari Truck – Migrateurs (2007) and Mumbai: A Laundry Field (2007) directly reference dire social circumstances, while Mandala: Zone of Zero (2004–10) and Bottari – Alfa Beach (Nigeria) (2001) reference religious coexistence and historical slavery respectively. And yet there is a warmth that we feel in their presence, a fortification of the utopia which, for Kimsooja, is still possible. There is no judgement, only a continuous opportunity for the good: the laundry field in the caste quarter in Mumbai can end at the stroke of a government pen; the mandala accentuates rhythmic commonalities, the potentialities of the ‘zero’, not the dogmatic differences; and empathy, she reminds us with an upside-down video view of the African beach from which slaves were shipped, can go a long way.

Opening as part of the 2018 Perth Festival, this is the first fully conceived and produced exhibition by PICA’s incoming Senior Curator Eugenio Viola. No stranger to Perth herself, Kimsooja – Korean-born, New York-based – has exhibited her work in 1997 and 2001 at the Art Gallery of Western Australia, as well as nationally, but this show feels like a different moment for PICA and a measured moment of focus for those familiar with the artist’s work.

The prevailing stillness of this exhibition is like the beginning of a shift in our collective consciousness that can happen at any moment and on the international scale; and with this, the curator and the artist remind us that exhibitions can be quiet utopian launch pads anywhere in the world.

Dunja Rmandic is an Associate Curator Projects at the Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth.