Finding a post-internet self

/In our current issue, 2020 ANCA Critic-in-Residence Sophia Halloway reflects on the ever greater importance that online forms of communication have come to assume in the past few months, as ‘a lifeline to our loved ones and livelihoods’ and ‘a source of connection’ to a world from which we have been separated by quarantines and self-isolation. In this new environment for the arts, innovative digital platforms created by museums and galleries across Australia – like Griffith University Art Museum’s ‘Lockdown Studio’, the Art Gallery of New South Wales’s ‘Together in Art’, and the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s ‘Artist Voice’ series – have become a regular feature of the Art Monthly Australasia blog. Halloway, however, asks us to turn our attention to the new forms of expression that artists have used and developed to map this unexplored frontier for ‘post-internet’ art.

Halloway defines this as ‘art “since” the internet rather than art “on” the internet’, revealing ‘a state of mind characterised by the ubiquity of internet culture’. This category of practice has, of course, been an emergent feature of the creative landscape for some time, but, under current conditions, has gained renewed relevance. Among the many opportunities for broadening artistic horizons made possible by the internet, Halloway draws attention to the new platforms for sharing work ‘without the usual gatekeepers of an elitist art world’, the ability to ‘loan’ digital recreations of valuable or fragile works to galleries that lack the resources required to borrow the original piece, and the capacity ‘to reach audiences who ordinarily wouldn’t walk in the front door of a gallery’. Those artists who had already started to engage with these post-internet opportunities, she asserts, ‘are uniquely positioned to continue practising in a COVID-19 world’. As current restrictions on movement and public gatherings seem increasingly likely to remain in place for the foreseeable future, many more will inevitably turn in this direction as they seek not only to maintain but to expand their artistic practice.

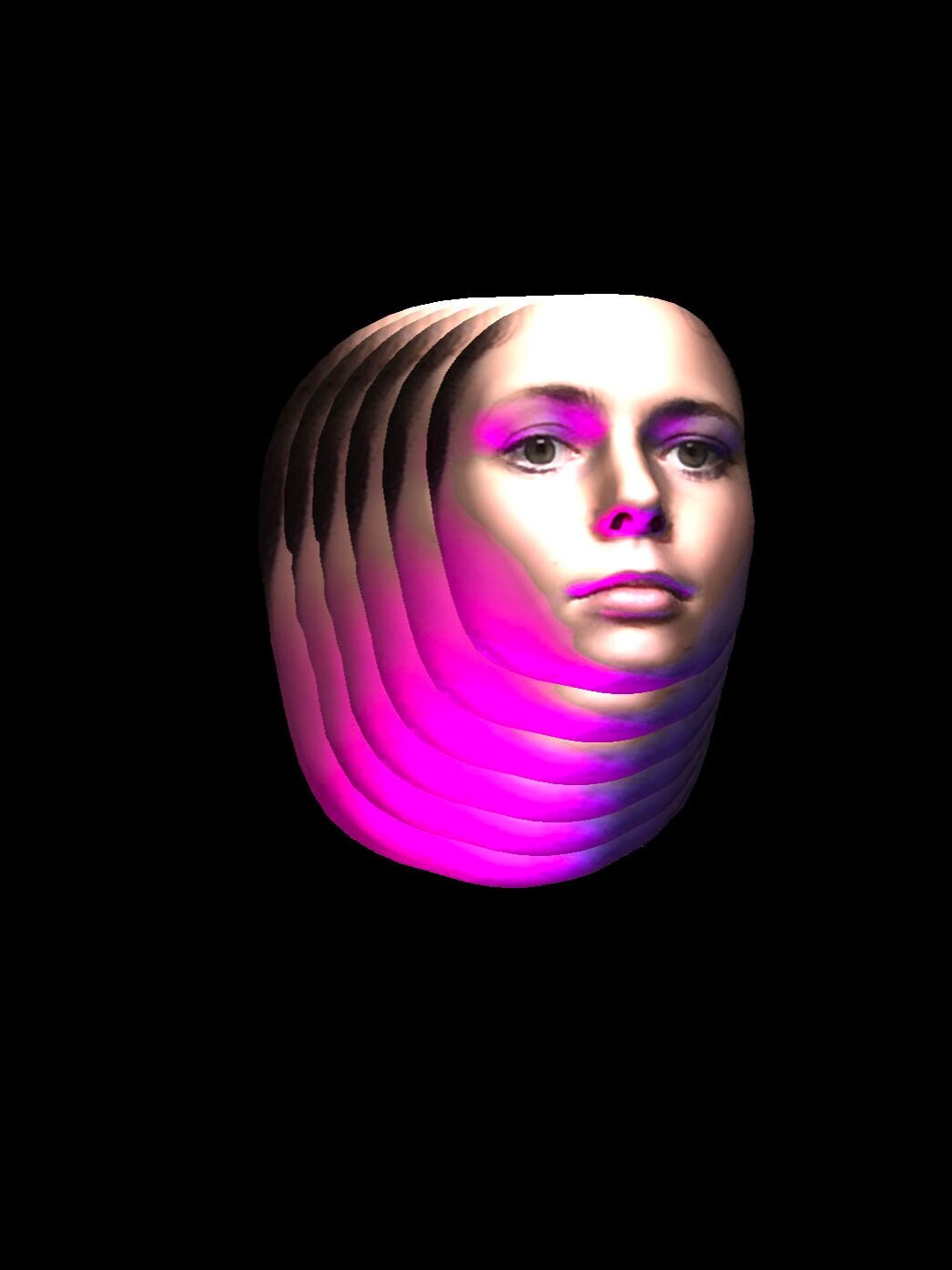

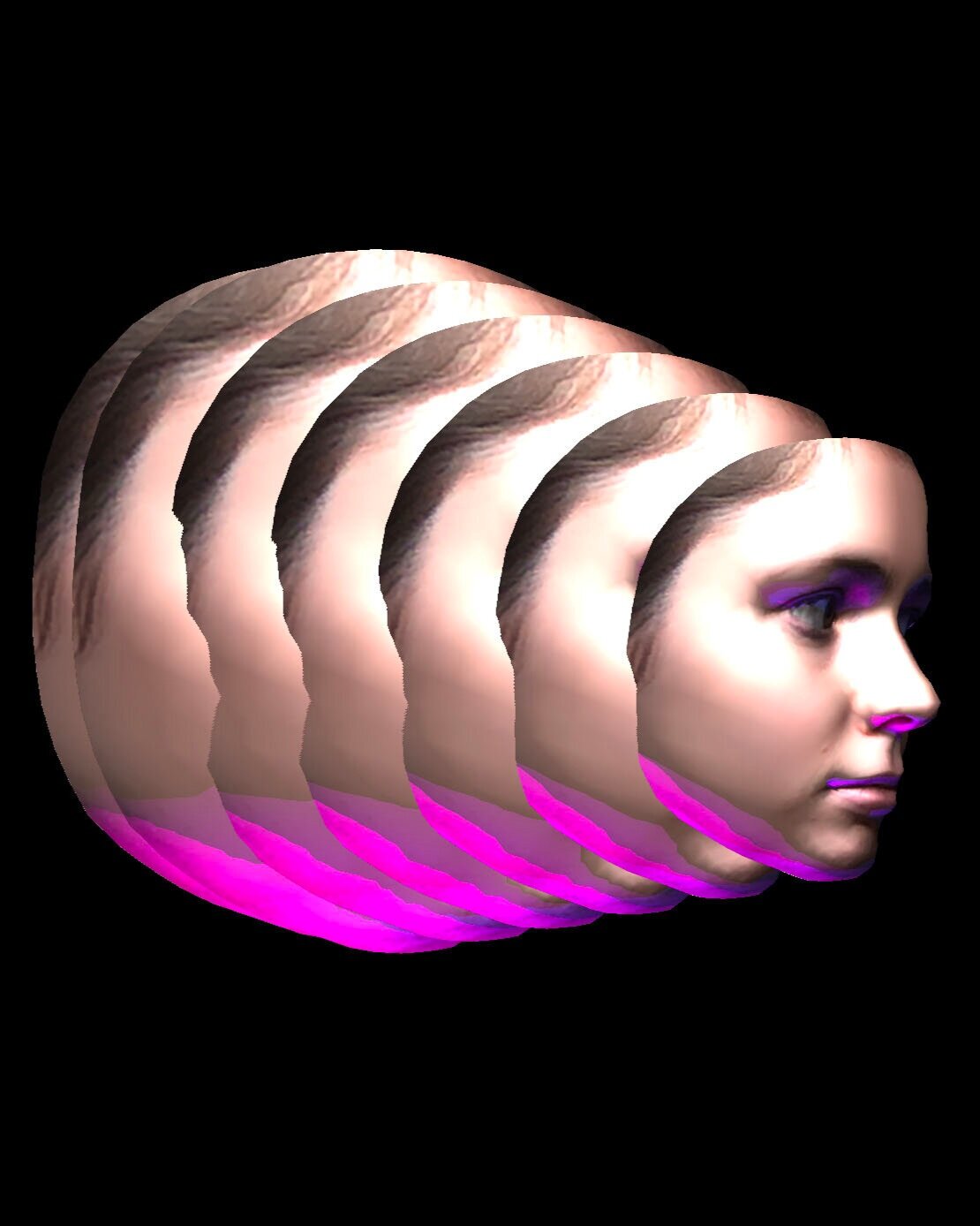

In her prescient summary of things to come, Halloway names Canberra-based artist and Australian National University PhD candidate Jess Herrington as a quintessential example of this new breed of post-internet artist. Herrington situates her practice primarily on social media, using her Instagram account (@jess.herrington) to share filters that augment the viewer’s (or user’s) reality by appending virtual objects to their face, looking back at them from the screen of their phone, laptop or tablet. Social media, Halloway writes, ‘has been criticised for distancing us from meaningful experiences in real life, with the sleek black mirror of our devices being like the glossy surface of Narcissus’s pool’. Herrington’s filters have transformed this ‘common expectation … that selfies are a form of self-commodification’ into an opportunity to ‘interrogate how we perceive ourselves on and offline’, to consider the limits of our identity and to construct new forms of selfhood. While museums and galleries seek to grow audiences and to foster public engagement with the works of art in their collections, artists like Herrington invite us to look within and to consider the personal role we can play in navigating safe passage beyond the current crisis.

Dr Alex Burchmore, Publication Manager