Bringing colour to forgotten histories in Gary Carsley’s ‘Chromophilia’

/Cultural institutions dedicated to the preservation and presentation of significant collections have been irrevocably transformed by the social and economic impact of COVID-19. Yet the changes now taking place in such institutions across the world cannot be attributed solely to the pandemic. Many have been years, even decades in the making. The need to adapt to extraordinary circumstances has, however, uncovered hidden fault lines and revealed new solutions for old arguments. Digitisation of collections and updating of websites with user-friendly interfaces, for example, has been ongoing since the turn of the millennium, but has advanced much more rapidly in recent months, as cultural institutions find themselves competing for a global audience alongside a growing range of other digital content providers.

Even an institution as tied to tradition as New York’s Institute of Classical Architecture & Art (ICAA) must adapt to survive in this rapidly evolving arts ecology. The ICAA has shown a readiness to embrace new avenues for communication and education with their online exhibition ‘Chromophilia’, an intervention into their historic plaster cast collection by Sydney artist and scholar Gary Carsley. Invited to respond, not to physical sculptures, but to the digital avatars of three casts gifted to the ICAA in 2004 by the Metropolitan Museum of Art – The Discobolus, Sleeping Ariadne and Demeter Ludovisi, replicas of Roman statues based on earlier Greek models – Carsley has created a suite of animations using image overlay techniques that mimic popular social media filters.

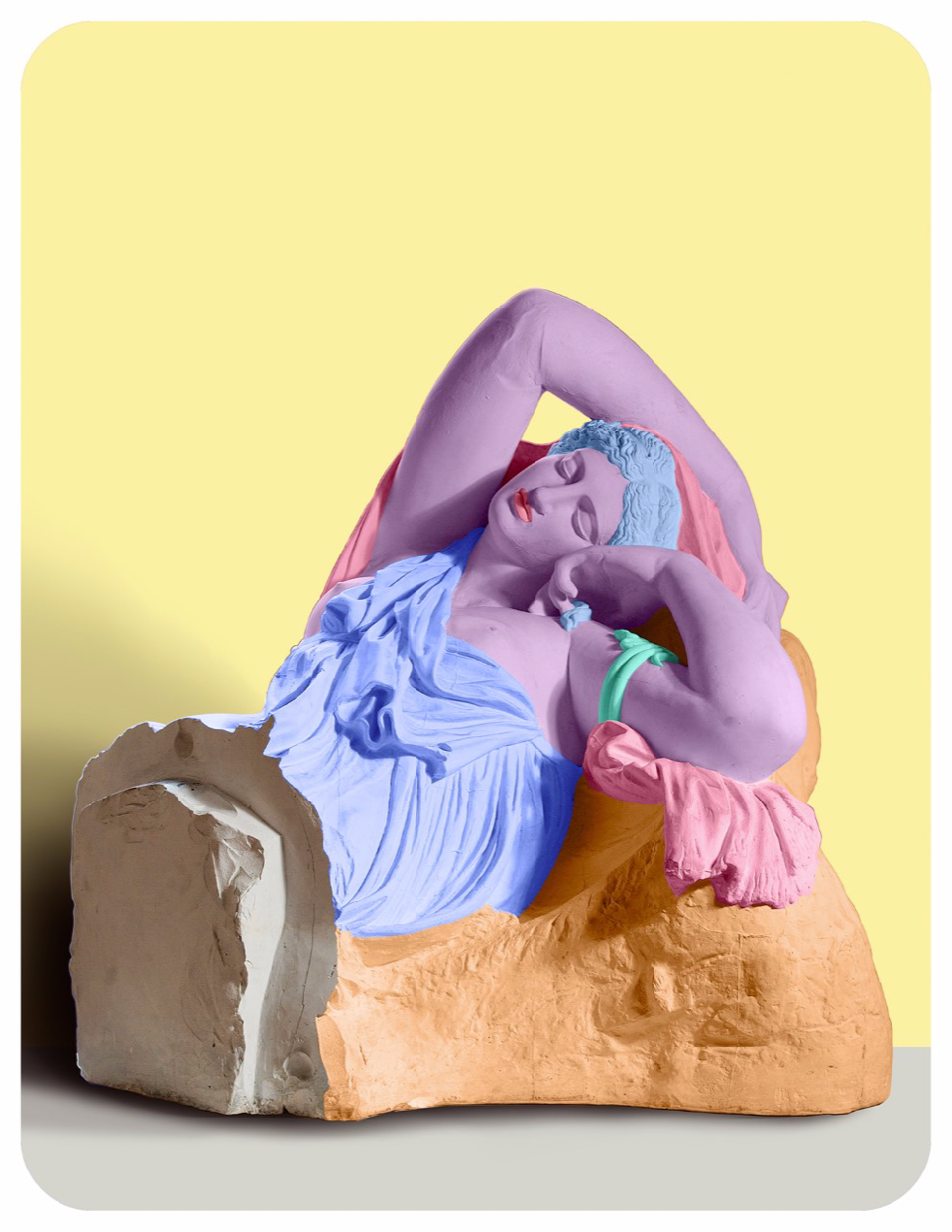

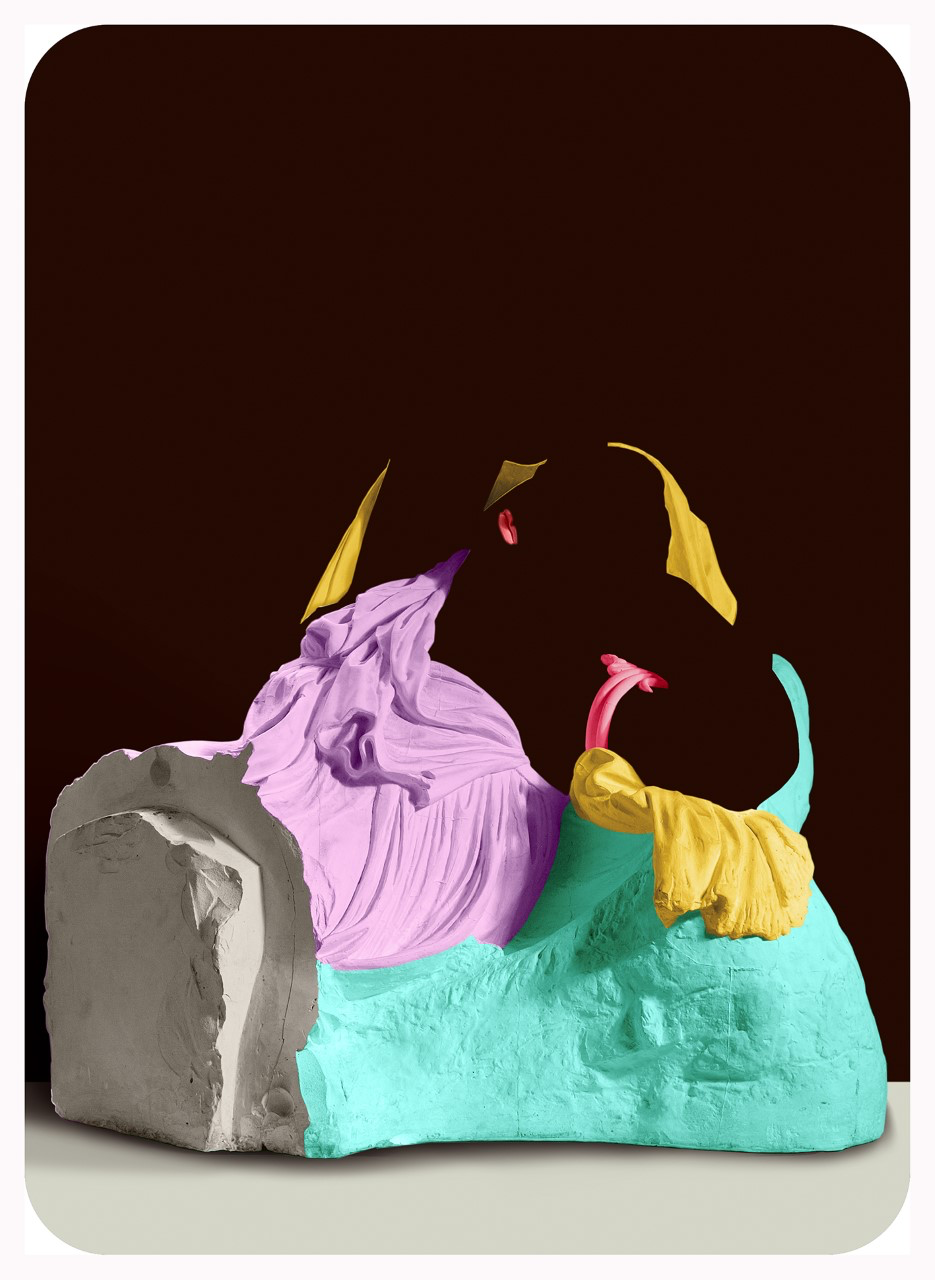

The partial Sleeping Ariadne, for example, gently slumbers, her chest rising and falling as the dark background against which classical sculptures are customarily shown lightens and fades from black to various shades of blue. Ariadne herself, caught in a moment of repose from which she will awake to discover that her lover Theseus has deserted her, also takes on new hues. She is saturated at first with a palette of lilac, green, yellow and pink, a transfusion of vivid colour that revivifies petrified flesh and fabric, gaining intensity as Singaporean composer Louise Loh’s ambient score builds to a crescendo. Yet this gentle reinvigoration abruptly transitions into a succession of feverish hues, the breath of the sleeping figure quickening as the insistent chiming of a cymbal seems to mark the passage of anxious thoughts and irrational visions until, at last, figure and background alike fade to black, leaving only her hair, lips and luxurious garments visible in the darkness.

Carsley’s intervention breathes new life into the ICAA’s pristinely white plaster casts, yet his project is not driven only by a desire to recreate the past in living technicolour, but to restore these casts to the multicoloured splendour of their ancient models. In the classical world, visitors to the website are informed, sculpture and architecture were ‘host to an explosion of colour, called polychromy’. The aim of this exhibition is ‘to reimagine what they would look like if they had never lost their original chroma’. In his artist statement, Carsley sets his project apart from other interventions into institutional collections in which artists or curators juxtapose objects ‘from different cultures or periods to challenge sanctioned histories by proposing alternatives’. Instead, inspired by online gaming, he seeks to reveal that which is hidden ‘in plain sight, [but] must be discovered, uncovered and interpreted’.

As such, ‘Chromophilia’ also draws attention to another development in cultural institutions that has been accelerated by the impact of the global pandemic. Plaster casts of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, although they appear aesthetically pure, are indelibly coloured by the ideologies and histories of European colonialism. The idealised forms of these whitewashed figures, and the veneration for a comparably idealised classical past that they represent, are inextricably tied to scientific and institutional rationalisations of racial prejudice. For Carsley, the project offered an opportunity to shed light on this history, and to remind contemporary audiences that ‘there is no such thing as a special group of people who can uniquely claim to be entirely without colour’.

In this, Carsley could be compared with English art historian Alice Procter, whose ‘Uncomfortable Art Tours’ of major museums and galleries are likewise intended to ‘unravel the role colonialism played in the broader material history of celebrated works … and [their] ideological aesthetics’. Inaugurated in 2017, Procter’s tours predate the pandemic and played a crucial part in a subsequent decision made by several of the institutions involved to introduce greater transparency in their labelling of artefacts stolen, looted or otherwise acquired in unethical circumstances. The closure of cultural institutions has not put an end to such calls for accountability. Rather, as in ‘Chromophilia’, the revelation of forgotten or hidden histories has gained greater visibility and accessibility as artists, curators and educators realise the full potential of online and digital resources.

Dr Alex Burchmore, Publication Manager

Gary Carsley’s ‘Chromophilia’ can be visited on the ICAA’s website through January 2021. The artist’s concurrent exhibition ‘ARBOUR ARDOUR’ is on display at Sydney’s Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery until 28 November 2020.