Dazzling duet: ‘Two Wings to Fly, Not One’ at Pakistan’s National Art Gallery

/Two Wings to Fly, Not One, exhibition install view, National Art Gallery of Pakistan, Islamabad, 2017; photo: Atif Saeed and Kamran Saleem

Borrowed from a Jalaluddin Rumi verse, the recent exhibition ‘Two Wings to Fly, Not One’ (which closed 31 May) paired two of Pakistan’s most important artists in the largest contemporary art exhibition ever shown at the National Art Gallery of Pakistan in Islamabad. The practices of Aisha Khalid and Imran Qureshi have evolved remarkably close together, and yet their approaches remain noticeably different: Khalid executes precise patterning to hide and reveal forms, while Qureshi’s expressive works take a looser style, moving between delicate lines and swathes of evocative colour. Over 50 works carefully balanced the different trajectories of their careers and some of the surprising shifts in their practices, while conveying how their works continue to converse with each other so intimately when side-by-side.

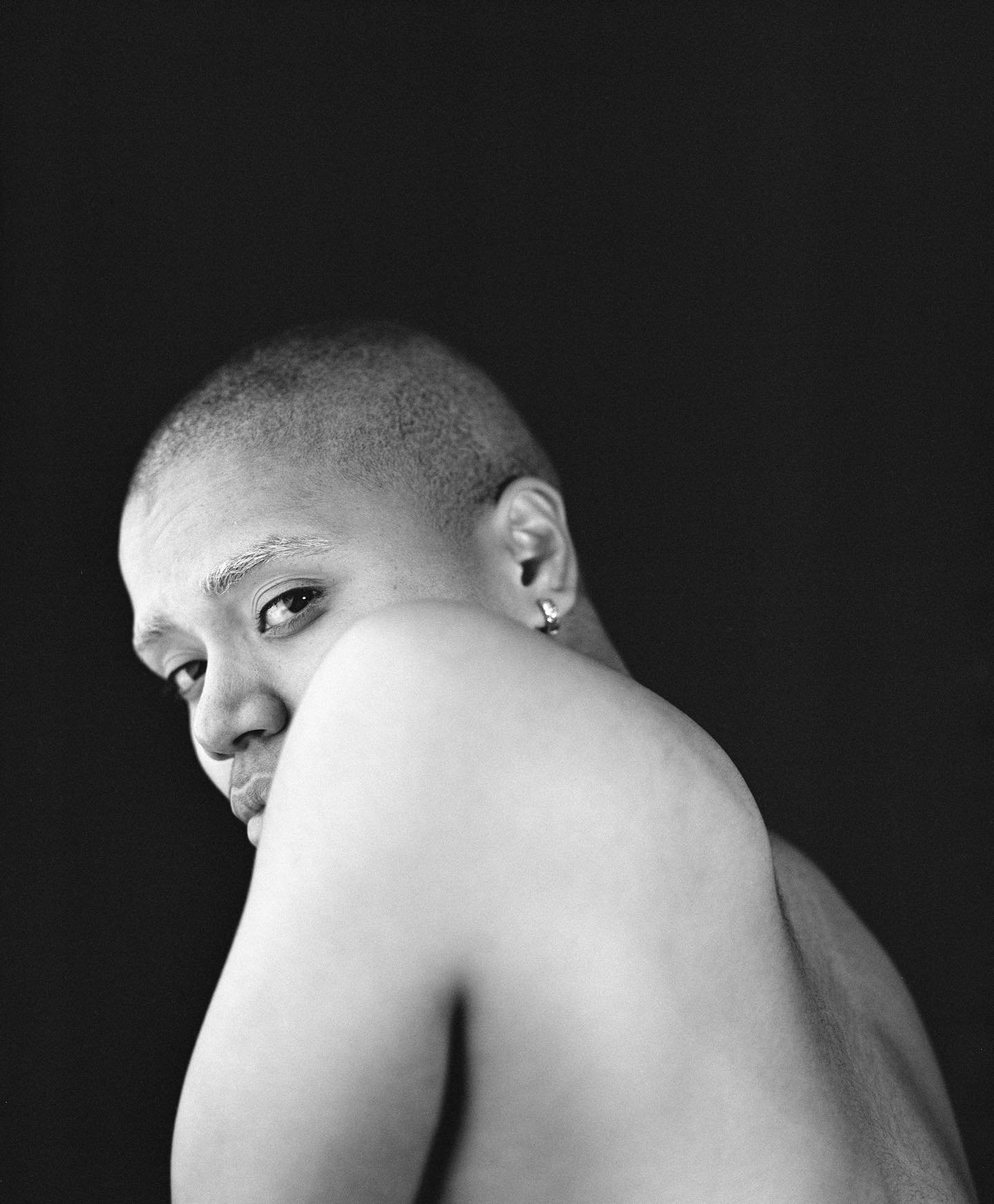

A rich selection of miniature paintings were dotted throughout the four gallery spaces, showing the great compositional and rigorous technical skill that have come to inform larger-scale works. However the exhibition was dominated by examples of both artists continuing to experiment and test the principles of the genre. Video works poetically drew on their creative processes, with Qureshi’s Rise and Fall (2014) revealing slow motion splashes of red ink that build to his layered works, and a second video showing the graceful movement of a piece of gold leaf floating in the breeze; while Khalid’s first ever performance formed the subject of her new video installation, documenting her gold needles rhythmically piercing through cloth in concert with a group of Sufi musicians.

The grand spaces of the 1989 modernist brick building provided multiple stages for the towering scale for which both artists are now known. Qureshi’s largest paintings to date were given centre stage, with striking bursts of burnished gold gradually fading into vivid reds and blues, while the centrepiece of the adjacent gallery featured Khalid’s immense pair of gold and silver pin tapestries draped either side of a column, cleverly referencing the ongoing conflicts in Kashmir in a medium that plays with the regional artform. In an adjacent courtyard Qureshi dramatically transformed a concrete amphitheatre with a scattering of painted flowers and splashes of red, similarly making a subtle reference to conflict and violence under the backdrop of the government buildings of Islamabad.

Khalid and Qureshi were among a generation of artists that had a major impact on contemporary art in Pakistan while studying miniature painting at the National College of Arts in Lahore in the late 1980s and early 1990s. They remain mentors and prolific artists in the Pakistani art community, and while their careers have taken them on different paths, they have come together to share their extraordinary parallel journeys in a duet that captures the essence of Rumi’s words.

Tarun Nagesh, Islamabad